Amending the Clean Water Act

When the House of Representatives reconvenes in September, they will likely vote on a collection of amendments to the Clean Water Act: H.R. 3898, which they’re calling the PERMIT Act (Promoting Efficient Review for Modern Infrastructure Today). It’s a bad bill and you should urge your representatives to vote against it.

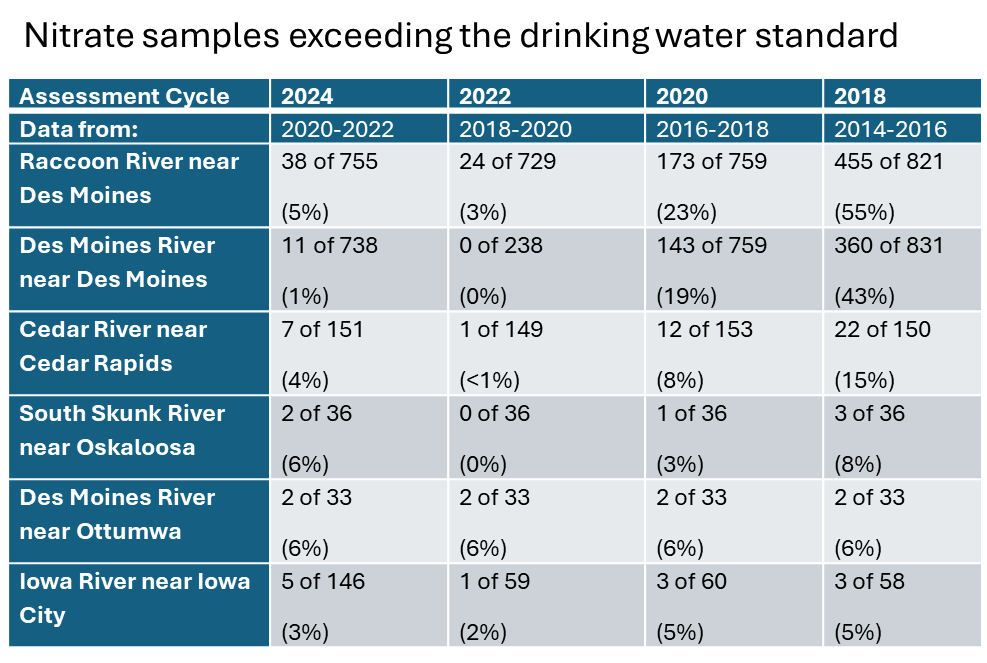

The Clean Water Act no longer works well in Iowa, because our largest remaining source of pollution is agricultural stormwater runoff, which has a special exemption. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources has been reluctant to put waters on the impaired list and write cleanup plans because they can’t enforce them. They have been reluctant to update standards because they think it will result in higher costs for small town sewage treatment plants without making any noticeable difference for water quality in rivers. I have a whole presentation about impaired waters if you’d like more details, but that’s the situation in a nutshell.

HR 3898 makes this worse. It expands exemptions for agricultural stormwater and pesticides without any provisions to encourage conservation. It mixes economic considerations into the process for setting standards and evaluating impairments. If there’s no widely available and cost-effective way to get a pollutant down to the level that science says is needed to protect aquatic life or drinking water, then the DNR would have to set a weaker standard, or delay setting standards. This would leave the public in the dark about the condition of our lakes and rivers.

There has been a long-running controversy over the extent to which the US Army Corps of Engineers and EPA can regulate construction in wetlands and waterways, which hinges on the definition of phrase: “Waters of the United States.” The Supreme Court recently ruled that many kinds of wetlands aren’t covered. This bill would exclude ephemeral streams, which had previously been considered on a case-by-case basis. I would be less worried about the impacts of these decisions if Iowa had state law requiring developers to avoid or mitigate wetland fill, like some of our neighbors do.

HR 3898 goes beyond clarifying a few exceptions to roll back what many people see as federal overreach. It also raises the threshold for general permits, making it easier to fill small wetlands even if they do have an obvious connection to navigable waters. It makes it harder for states to block pipeline projects. Amendments by Democrats to study the impacts of the bill or mitigate them with a no-net-loss policy were rejected and the bill passed out of committee on a party line vote.

The one good thing about the bill is it’s a reminder that Congress does have the ability to fix outdated laws. What we now call the Clean Water Act are the 1972 and 1977 amendments to the 1948 Federal Water Pollution Control Act. Those amendments made a big difference for waters that were once polluted by sewage and industrial waste. This summer, I paddled on a beautiful and relatively clean stretch of the Shell Rock River with a canoe partner who grew up in the area and recalled how foam used to float down the river from meatpacking plants in Minnesota. The law was amended again in 1981, 1987, and 2014. It could use another amendment to cut red tape while better addressing today’s water quality challenges, but this isn’t it!