South Skunk River Cleanup – Spring 2024

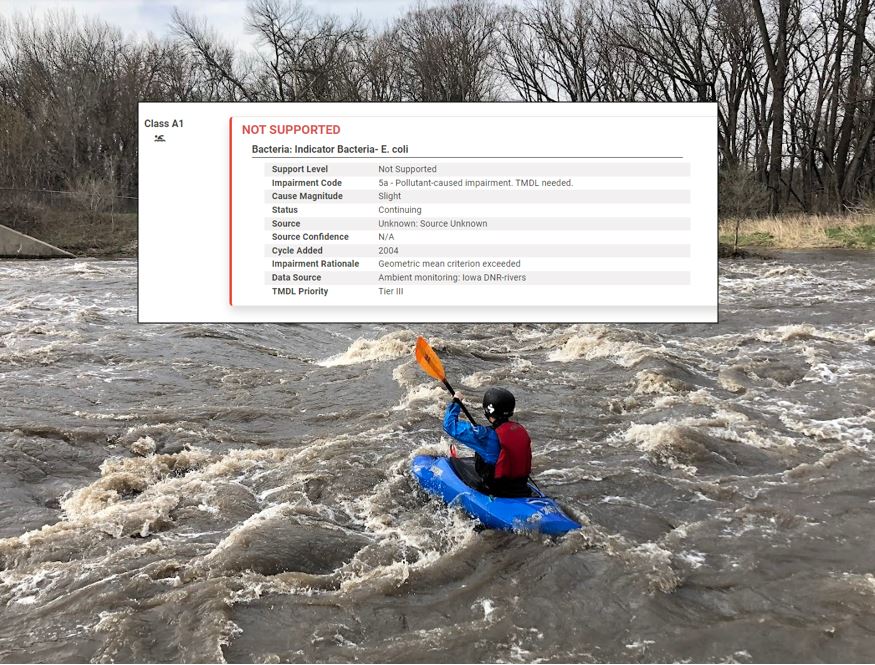

On April 20, volunteers cleaned up trash along a 3.5 mile stretch of the South Skunk River in Ames, from River Valley Park to S. 16th St. Several people also ventured up Ioway Creek, and those who stayed on shore had plenty to do. The fast current meant we arrived at the destination earlier than expected, where we set to work clearing out an abandoned campsite. Judging by some of the items we found, families with children had stayed there, so please support organizations that work on affordable housing and provide emergency assistance. In between stops at sandbars to retrieve trash, there was ample opportunity to enjoy the river. The fast current made for a fun ride through some mini-rapids (nobody tipped!), and we saw kingfishers, great blue heron, and a bald eagle.

Chilly weather (high of 48 degrees) may have dampened some of the initial enthusiasm for our spring 2024 creek cleanup event. We went from having not enough canoes for everyone who registered, to several extra canoes. With a smaller flotilla than last spring, we can’t claim a record breaking haul, but we did remove more more trash per person! In addition to the usual cans, bottles, plastic and styrofoam, finds included four tires, seven empty propane tanks, a shopping cart and a microwave.

- April 2023: 3,020 pounds/40 people = 76 pounds/person

- April 2024: 2,100 pounds/16 people = 131 pounds/person

Tony Geerts likely exceeded that average figure, arriving at the take out point with a big tractor tire. It would have made a great picture, but as I was rushing up to capture the moment, my phone slipped out of my hands and into the river! Fortunately, other people took photos and have shared them with me.

Assembling the tools, canoes, food, and people was a collaborative effort involving Prairie Rivers of Iowa, the City of Ames, Story County Conservation, the Skunk River Paddlers, and the Outdoor Alliance of Story County. Thank you to all who volunteered, organized, and supported the event.