Six Tips to Enjoy Iowa Lakes

There is no better way to relieve stress and get an attitude adjustment than spending time by a lake, whether you’re fishing, swimming, paddling, watching wildlife, or watching the sunset. But it’s hard to enjoy a lake if it’s choked with toxic blue-green algae. Cleaning up Iowa lakes so we can enjoy them will require some shifts to our attitudes.

1. Don’t Panic

I’m sure you’ve all heard about the “brain-eating amoeba” Naegleria fowleri. Iowa and Nebraska both had their first cases in 2022 (both fatal), contracted at the Lake of the Three Fires and the Elkhorn River, respectively. While scary, cases are also extremely rare. Nationwide there have only been 157 cases in the past 60 years, concentrated in the South. And even where the amoeba is known to be present, there are ways to enjoy the water while minimizing risk.

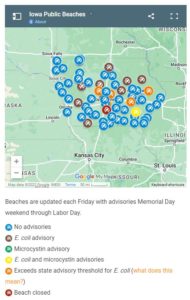

2. Check Where the Beaches are Cleanest

Iowa Environmental Council maintains a map and puts out a weekly report showing where there are beach advisories. The map also shows many lakes with no advisories (the blue umbrellas). For example, in Story County, the beach house at Hickory Grove Lake is sometimes closed due to high E. coli levels, but at Peterson Park, E. coli has been consistently below the detection limit. Not every lake in Iowa is hopelessly polluted, and even the most troubled lakes will have their good days. Take advantage of them!

3. Help clean up dirty lakes at the local level

Having spent some time enjoying a clean lake, hopefully, you are in a better frame of mind to tackle the not-so-clean lakes. There are lake improvement efforts all over the state that need the support of taxpayers or the help of landowners in the watershed. For example, Story County is planning a complete renovation of McFarland Park Lake, which recently suffered an algae bloom and fish kill.

“The renovation will: remove sediment, stabilize shoreline, increase lake depth, and improve lake habitat for aquatic plants and animals. Work will increase overall health of the lake, reduce the number of fish die offs in the future, and improve recreational opportunities.”

4. Keep clean lakes clean at the state and national level

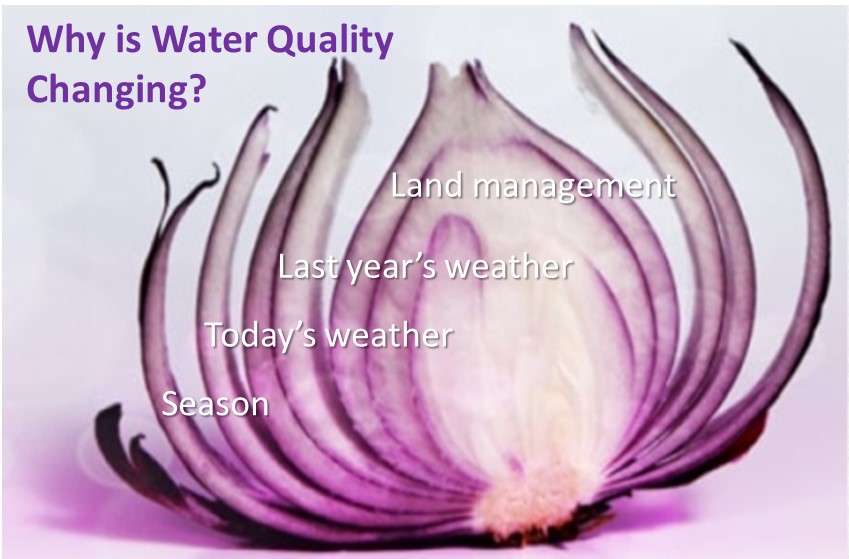

It does no good to dredge out a lake if farmers in the watershed are going to plow up the hillsides around it. This is what happened to Lake of the Three Fires, as related by Chris Jones. When a third of the county was converted from pasture to corn ground, the lake gradually returned to its former shade of brown. We can’t do much about naturally occurring amoebas, but we can take a hard look at the policies, business and purchasing decisions, and attitudes that shape farming practices across Iowa.

5. Think globally, act locally

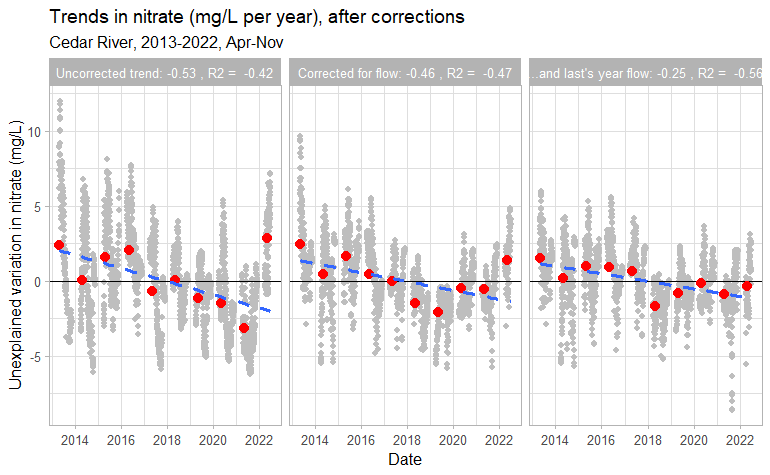

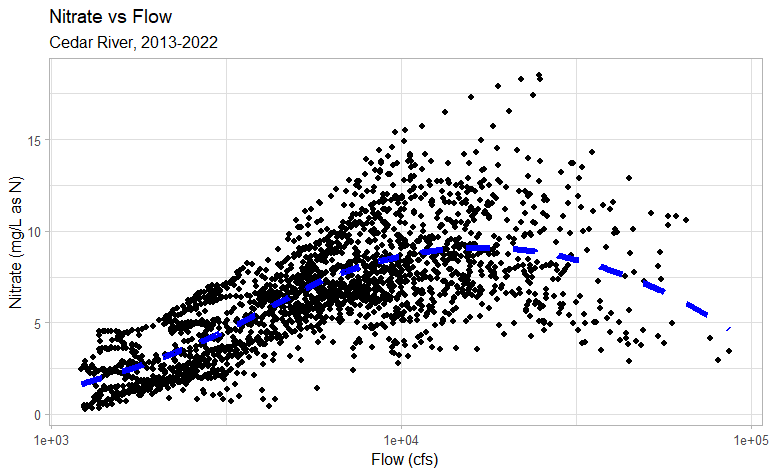

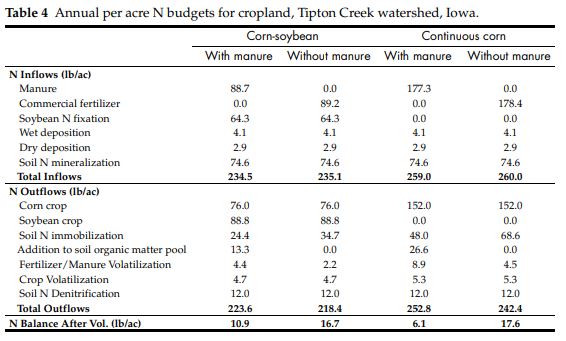

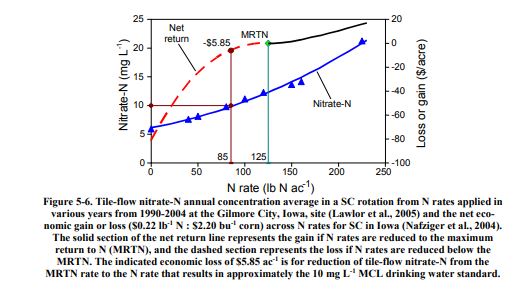

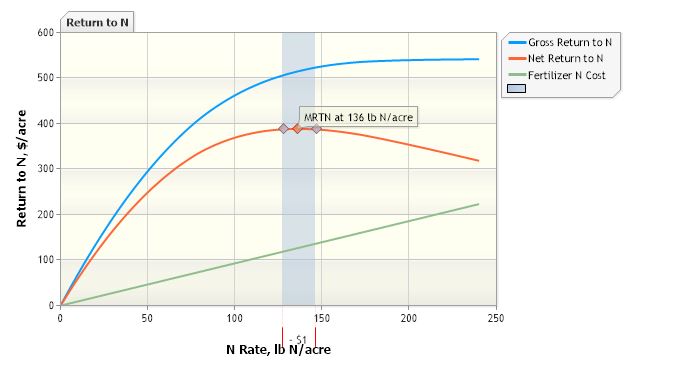

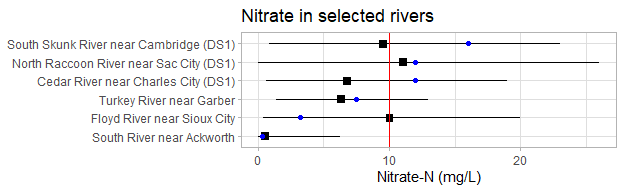

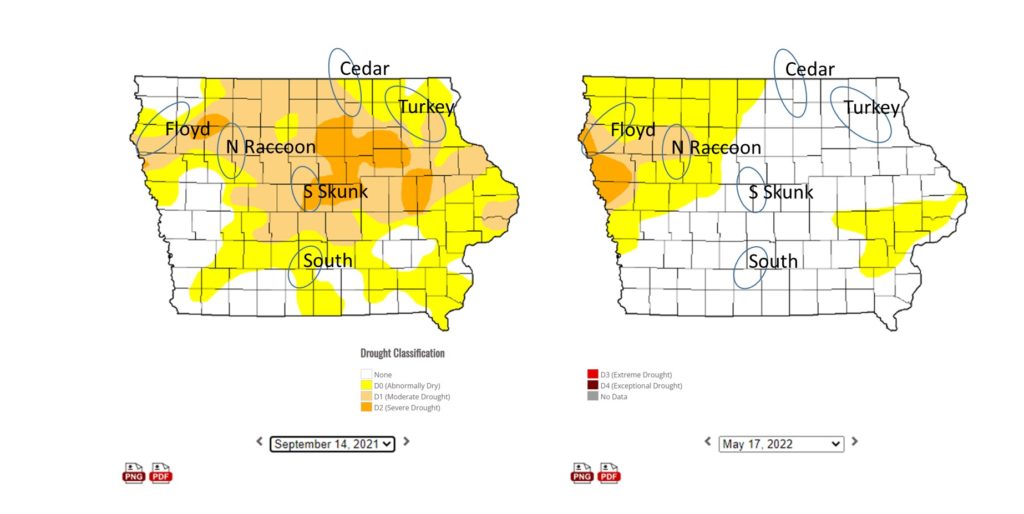

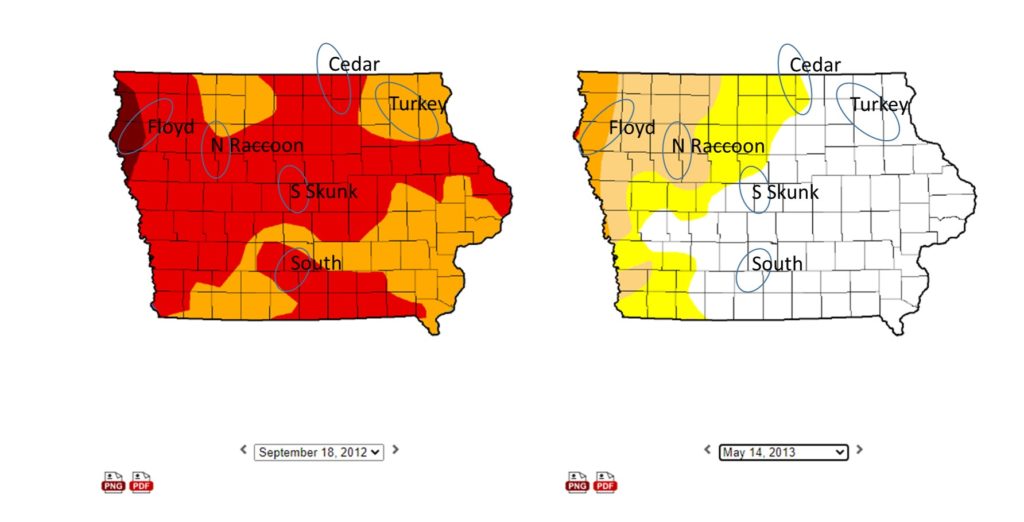

The warmer the water, the more cases of Naegleria fowleri. The same goes for harmful algae blooms, a much more common problem in Iowa that is getting even more common. If we don’t reduce our greenhouse gas emissions fast, hotter temperatures and more intense spring rainstorms will continue to worsen our water quality woes. Fortunately, there are opportunities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Iowa while at the same time improving water quality in the short term by planting more deep-rooted perennials and cover crops, building up organic matter in the soil, and using less nitrogen fertilizer.

6. Share your favorite water memories

A friend was visiting from out-of-state when I wrote this article. A family vacation to Iowa of course included time with the grandparents and a visit to the Iowa State Fair, but he also set aside time to take his kids wading in Ioway Creek, where they caught minnows and marveled at the weirdness of dragonfly nymphs. For my friend, time spent outdoors in creeks and lakes was an essential part of growing up in Iowa, and he wanted his children to share that experience.

What a wonderful mindset to cultivate as we work to improve water quality!