The Des Moines Waterworks was forced to use their nitrate removal system for the first time in five years. Our spring snapshot found high nitrate concentrations in streams across Story County. On my way to speak at the CCE Environmental Expo in Mitchell County, I dipped a test strip in the Cedar River near Osage and measured 16 mg/L. Looking at the Iowa Water Quality Information System there’s orange (nitrate greater than 10 mg/L) across much of the state and spots of dark red (nitrate greater than 20 mg/L) in Story, Hamilton, and Hardin counties. What’s going on?

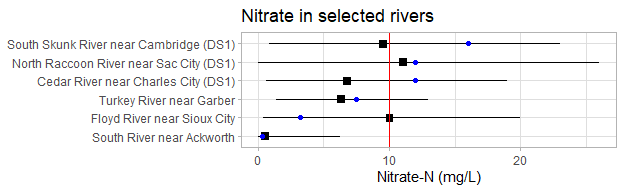

Well, differences in land use, soils, topography, and farming practices make for strong regional differences in water quality. For some streams like the North Raccoon River, this is a return to normal. For some streams, like the Cedar River, current conditions are unusual. To illustrate this, I’ve invented my own graph, which compares highest nitrate concentrations observed this spring (the blue dot) to the entire 10-20 year record (a black band showing the range, and a black square showing the median). The data comes from Iowa DNR’s Ambient Stream Monitoring Network; I will update these graphs once June data is available. A sampling of sites is shown at right, but the entire graph can be downloaded as a PDF here.

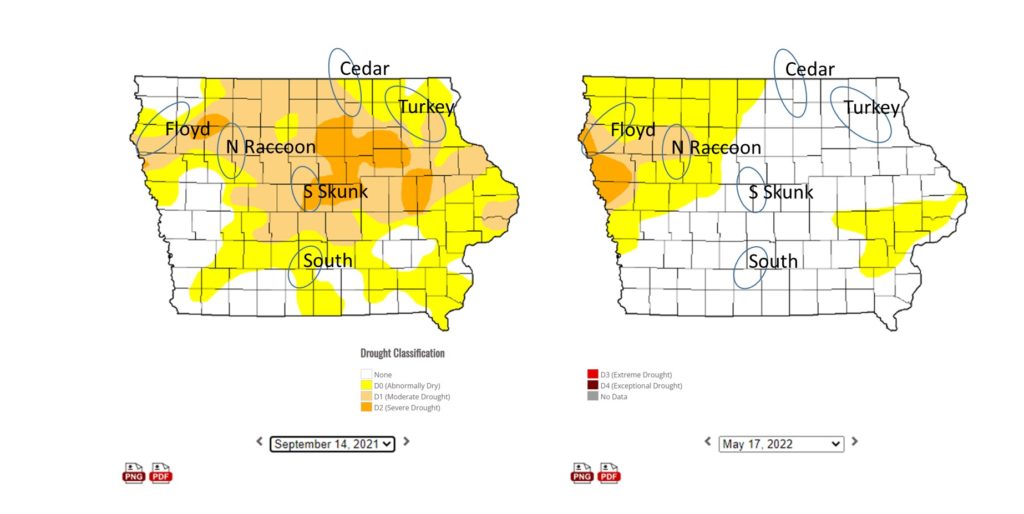

Northwest Iowa is still suffering from drought, and that means the Floyd River near Sioux City (which usually has some of the highest nitrate concentrations in the state) is barely flowing and has very low nitrate concentrations. As we saw last year, nutrient concentrations tend to be low during dry conditions except where there is a strong influence from point sources of pollution. Most of the rest of the state is back to normal, and nitrate that accumulated in the soil during two dry years is now getting flushed out. These maps are taken from the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I’ve drawn in the approximate location of the watersheds for the monitoring sites in my example.

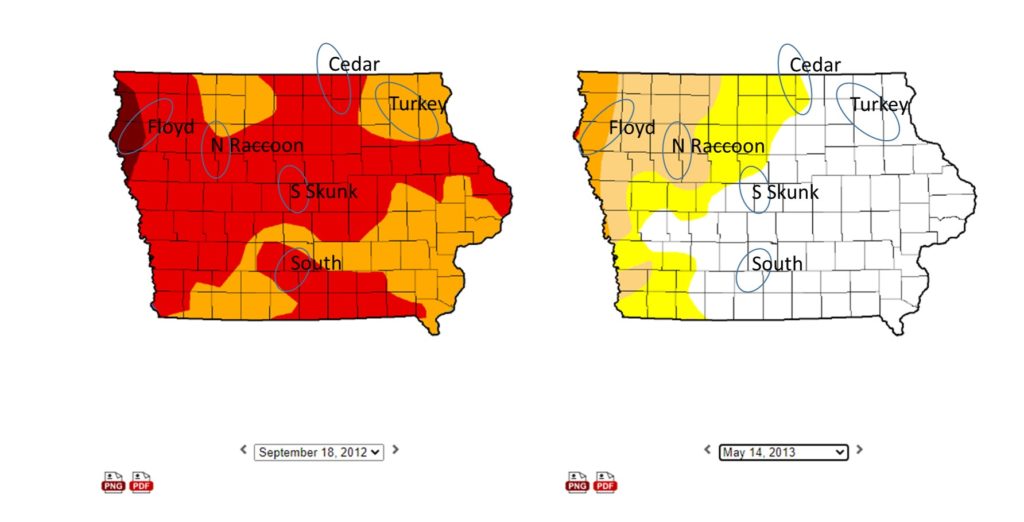

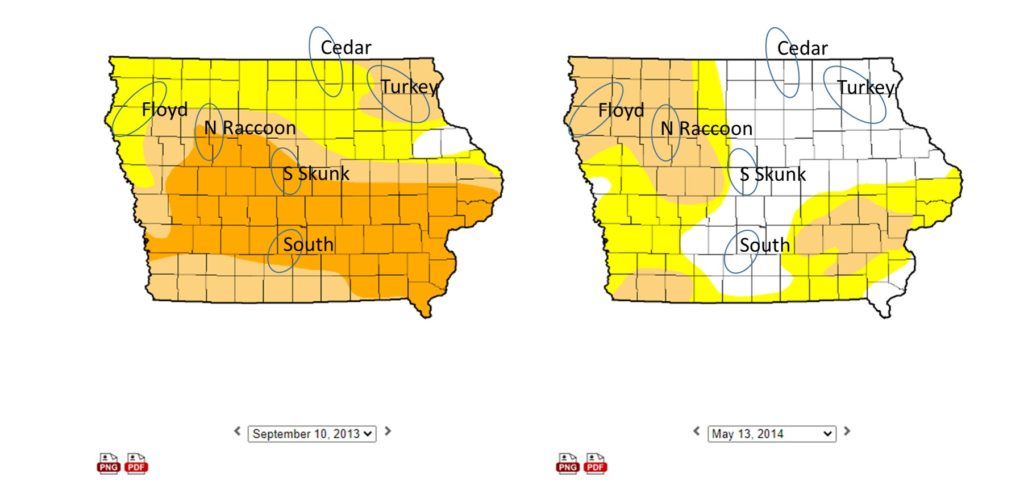

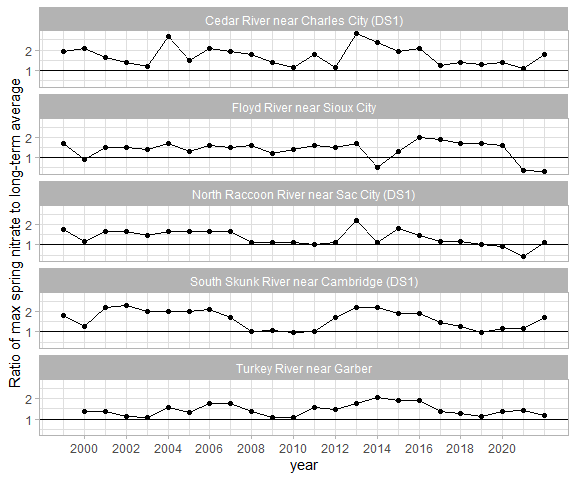

“Weather whiplash in agricultural regions drives deterioration of water quality.” That’s the title and conclusion of a paper that studied previous episodes when a wet spring followed a dry summer and fall. The 2012 drought was much more severe than 2021, impacting yields so that less nitrogen was taken up by the crop and removed in the grain, and maybe that’s why nitrate in 2013 and 2014 was so much higher than it is now. I’ve compared spring highs for several sites and years, normalizing by the long-term average. It’s not clear to me whether weather whiplash increases the overall mass (load) of nitrogen that gets washed away, or just alters the timing (moving in one year what would have been parceled out over two), but high concentrations are a concern for communities like Des Moines and Cedar Rapids that get their drinking water from a river or river-influenced wells.

I’m procrastinating on the work I’m supposed to be doing because “Hey look! Data!” and I have to satisfy my curiosity. If you’d like to see us do more water quality analysis beyond Story County, let us know, and support us with a charitable donation so it can become work I’m supposed to be doing!