On any field in Iowa, cover crops will improve soil health, sequester carbon, and prevent nutrients from washing down to the Gulf of Mexico. There are at least six situations where cover crops can add to the farmer’s bottom line, but in other situations, or to help encourage farmers to make that initial investment and get through the troubleshooting stage that comes with any new practice, public cost sharing can make a difference. Most taxpayers I talk to are quite willing to pay farmers who are employing conservation practices for the ecosystem services they provide. But we either can’t afford to or aren’t willing to invest at the scale needed to achieve universal adoption of cover crops and other conservation practices, and that means we have to make some decision about where to invest first, so as to get the most nutrient reduction (and hopefully carbon sequestration, soil protection, flood reduction, and other benefits) for our buck.

Most of those discussions are way above my pay grade. I suppose the legislators who draft the federal farm bill and the NRCS bureaucracy set payment rates and application scoring criteria for EQIP and other cost share programs. Iowa’s Water Resource Coordinating Council picked priority watersheds that can get special funding.

Planning at the local level can also influence where conservation investments are made. However, it’s not always clear what influence a Watershed Management Authority actually has over where 1000 acres of cover crops gets planted, or why it’s better to plant them in one part of a county rather than another. Same goes for other conservation practices. Here are 5 possibilities.

1. Plant cover crops where they can protect a local lake or water supply

In addition to Gulf Hypoxia, phosphorus that washes off the land is causing algae blooms in many of Iowa’s lakes. Overnight, these algae blooms can use up the oxygen that fish and other aquatic critters need to breathe. Some kinds of cyanobacteria can produce toxins that can harm people and pets. Algae blooms are nuisance for those who would like to swim, fish, boat, or water-ski in those waters. We can address two problems at once if those 1000 acres of cover crops are planted in the watershed of Hickory Grove Lake, Saylorville Lake or other water bodies suffering from an excess of green.

In addition to Gulf Hypoxia, nitrogen that washes off Iowa farmland can cause a problem for cities that pull their water from a river, or from wells close to and influenced by a river. The Des Moines Waterworks and the Raccoon River watershed have rightly gotten a lot of attention, but other cities in other watersheds (like Boone, on the Des Moines River) also are dealing with high nitrate in their source water. Cover crops in the right watersheds can help protect those water supplies.

Nitrogen and phosphorus can also cause algae blooms in creeks and rivers, but the science is more complicated than in lakes, and not often done. For example, while the Squaw Creek Watershed Management Plan demonstrates that nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the creek are high, it does not make the case that meeting our nutrient reduction goals will protect drinking water, improve fisheries, make for safer recreation in Squaw Creek. Maybe that’s a safe assumption, but I honestly don’t know.

2. Plant cover crops where they can reduce the most nitrogen

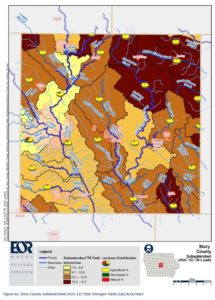

Here’s a map of nitrogen load by HUC-12 watershed in Story County, based on landcover. This kind of model would be handy if you wanted to guess which stream has higher nitrate levels at its outlet. If I plant 1000 acres of cover crops south of McCallsburg (in the “Drainage Ditch 81” hydrologic unit) will I get more nitrogen reduction than if I plant them west of Ames (in the Squaw Creek-Worrell Creek hydrologic unit)? Nope. The pounds/acre estimate here is for the whole watershed, and it’s based purely on landcover in that watershed. Unlike the larger watershed, a field west of Ames wouldn’t be 20% developed, it’d be 100% agriculture, so with this model we can’t assume it’d be different than a field anywhere else in the county. More sophisticated computer models like SWAT or SPARROW incorporate things like soils, slope, and county-level fertilizer sales as well as landcover, but it’s hard to tell which of those things is driving the results.

Other models like the Nutrient Tracking Tool are field scale, and can be used for this kind of prioritization. Running through some quick scenarios, I estimated that cover crops on a tile-drained field in the Squaw Creek watershed could prevent 9 lbs/acre of nitrogen loss each year, versus 3 lbs/acre in an undrained field in the watershed. Computer models can be helpful, if we’re clear about their purpose and limitations.

3. Plant cover crops where they can reduce the most phosphorus and sediment

Cover crops have gotten more traction in hilly southern Iowa, where soil erosion is a more visible problem and no-till is common. From a standpoint of tons of soil erosion prevented, or pounds of phosphorus loss avoided, it makes sense to plant on fields with steep slopes and erodible soils. Models like RUSLE can be helpful for this.

4. Plant cover crops where their water quality benefits can best be measured

1000 acres of cover crops will make a bigger splash in a small watershed than in a big one. A small change in water quality is difficult to detect. Just like a poll that talks to a small number of people has a margin of error, a water testing program that samples only 12 or 24 days out of the year will have some uncertainty attached to the results. I’ll be talking more about “minimum detectable change” in future posts, but suffice to say that margin of error is usually closer to 10 or 20 percent than 1 or 2 percent. That means we need to give some thought to where conservation practices will be located relative to long-term water monitoring sites if we hope to document their effects with water monitoring.

| Location of monitoring sites in Story County, and agency monitoring | Row-cropped acres in watershed | Expected N and P reduction at monitoring station from 1000 acres of cover crops in watershed |

| CREP wetland inflow (Conservation Learning Labs) | 1,270 | 23.62 % |

| Walnut Creek @ 530th Ave, near Kelly (USDA) | 3,756 | 7.99% |

| Onion Creek @ Reactor Woods, Ames (ISU) | 10,104 | 2.96% |

| E. Indian Creek @ S27 (SCC/PRI/Ames) | 63,852 | 0.47% |

| Squaw Creek @ Moore Park (IIHR) | 99,919 | 0.30 % |

| Squaw Creek @ Lincoln Way (SCC/PRI/Ames) | 107,775 | 0.27% |

| South Skunk River @ Riverside Drive (DNR) | 162,718 | 0.18% |

| South Skunk River @ 280th St, Story County (DNR) | 297,547 | 0.10% |

5. Plant cover crops where it is most cost-effective for the producer

We do some of this unintentionally. A farmer who can figure out how cover crops will make financial sense for their operation–cutting a pass for weed control or loosening compaction, providing forage for cattle, or protecting yields in wet or dry years–is more likely to sign up when the cost share being offered is $25-$35/acre. Those that think they will lose money will pass until we offer better incentives–for example, Maryland was paying up to $90/acre and has gotten more takers.

This is also the idea behind “precision conservation” promoted by Land O’Lakes and other retailers. With precision yield monitoring, conservation practices like wetlands, prairie strips, or buffers can be placed so as to minimize lost revenue. Poorly draining or steep parts of a field might actually cost more to plant, till, and fertilize than it generates in revenue, so farmers could install conservation practices and even come out ahead.

That’s 5 ways to get more conservation bang for our buck. Let’s be more clear about which of these we’re hoping to achieve when we do watershed planning, and more creative about how we support good stewardship.

Does this make sense? Are there other ways to be more cost-effective with conservation? Leave a comment!