In December of 2024, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) proposed adding the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) to the threatened species list under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). You can read their press release here. As part of the proposal, the agency also introduced a proposed 4(d) rule and a critical habitat designation focused on key overwintering sites in California. Typically, the U.S. Department of the Interior finalizes ESA listing decisions within one year of a proposal. However, a year later, no final ruling has been issued. Instead, we have less than that, we have a promise that maybe someday they will decide on it, keeping this incredibly important species in regulatory limbo, along with many other species awaiting listing or delisting decisions under the ESA.

This delay is only the latest chapter in a long and complex history surrounding efforts to protect the monarch butterfly. In fact, this iconic pollinator has been under consideration for ESA listing for more than a decade.

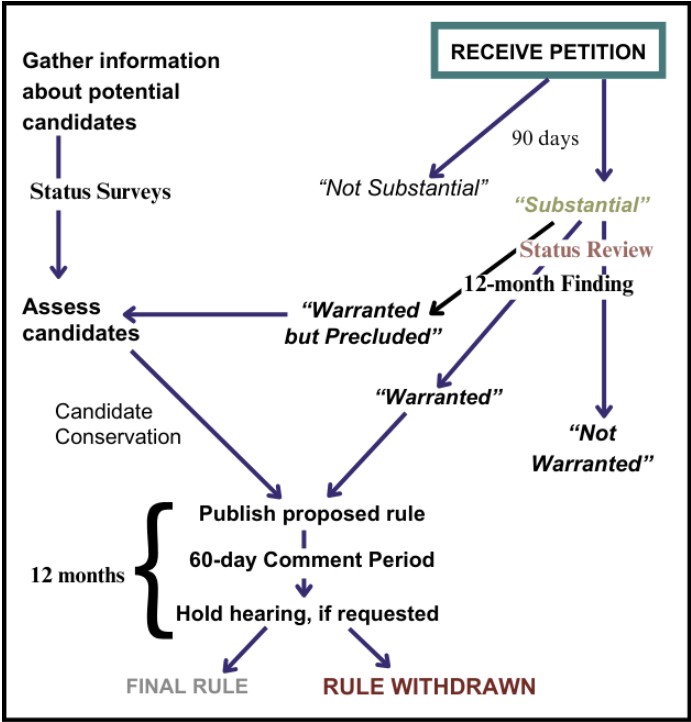

This is a flow chart from the US Fish and Wildlife Service showing the process for getting listed under the Endangered Species Act.

The saga actually started in August 2014 when a petition was filed with the USFWS from several reputable organizations, including Xerces Society, the Center for Biological Diversity, Center for Food Safety, and Dr. Lincoln Brower. They requested that the Monarch be listed as a threatened species with a 4(d) rule. Essentially, a 4(d) rule allows for continued conservation activities like monitoring, tagging, and rearing for educational purposes while still having protective actions in place.

In December 2014 the USFWS released a 90-day finding on the proposal . They “found the petition presented substantial scientific or commercial information that indicated listing the monarch may be warranted (79 FR 78775) and initiated a range-wide status review.” They proceeded to issue 12-month findings on the petitions.

You would think that would lead to a decision in 2015, however more research was requested and they actually took 5 years to create an assessment of population trends, threats, and consult with stakeholders. Granted, collecting data takes time and isn’t always the easiest to sort through or coordinate. While the research was being done, the Monarch was flying its way into the hearts of millions. Classrooms, communities, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) were banding together to create habitat for the beloved butterfly. Many concerned individuals were planting milkweed, reducing pesticide use, tagging Monarchs, and planting flowering native plants.

Over the next five years, USFWS conducted extensive analyses while monarch conservation gained widespread public attention.

Finally in September of 2020, the USFWS published their findings in the Monarch Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report. In this report they assessed the historical and current (2020) distribution of monarch populations, their status and health, identified key drivers of their health/decline, and their resiliency. Three months later, in December 2020, the USFWS announced their decision on listing the Monarch Butterfly under the ESA. They determined that the monarch should be listed as an endangered species, HOWEVER it was precluded due to higher-priority listing actions for other species that were in greater danger of extinction. The Monarch was categorized as a candidate species and the USFWS will review its status each year until it is finalized and published as a notice in the Federal Register, assuming it was still warranted.

In December of 2024, just a little over a year ago, the Monarch Butterfly was once again proposed as threatened under the ESA, along with a 4(d) rule and a critical habitat designation. This would have been a significant step in protecting the monarch butterfly. For 90 days following this proposal (Dec 12, 2024 – Mar 12, 2025) a comment period was open to the general public. Then the comment period was extended for another 60 days, meaning it ended in May 2025. Comments are essential to the proposal process and allows invested parties, such as scientists, organizations, individuals, and volunteer groups. Prairie Rivers, as well as many other conservation organizations, sent in a comment in favor of listing the Monarch as Threatened. The USFWS received more than 186,000 comments during this period.

USFWS generally has up to one year after a proposal to review comments and data before issuing a final rule. That rule may modify the original proposal or finalize the listing as proposed, after which it is published in the Federal Register and takes effect within 60 days. This listing would ensure the development of a recovery plan and provide clearer guidance for conservation actions.

As of December 15, 2025, roughly one year after the proposal, no final decision has been made. Recently, the Department of the Interior updated an agency rule list suggesting delays in the timeline for monarchs and other species awaiting listing/delisting actions to the ESA. The final rule for listing the monarch is now categorized as “Long-term Actions”. This means that the agency does not expect to act within the next year. Now, at the earliest, a final decision for the monarch would be the fall of 2026, at the earliest.

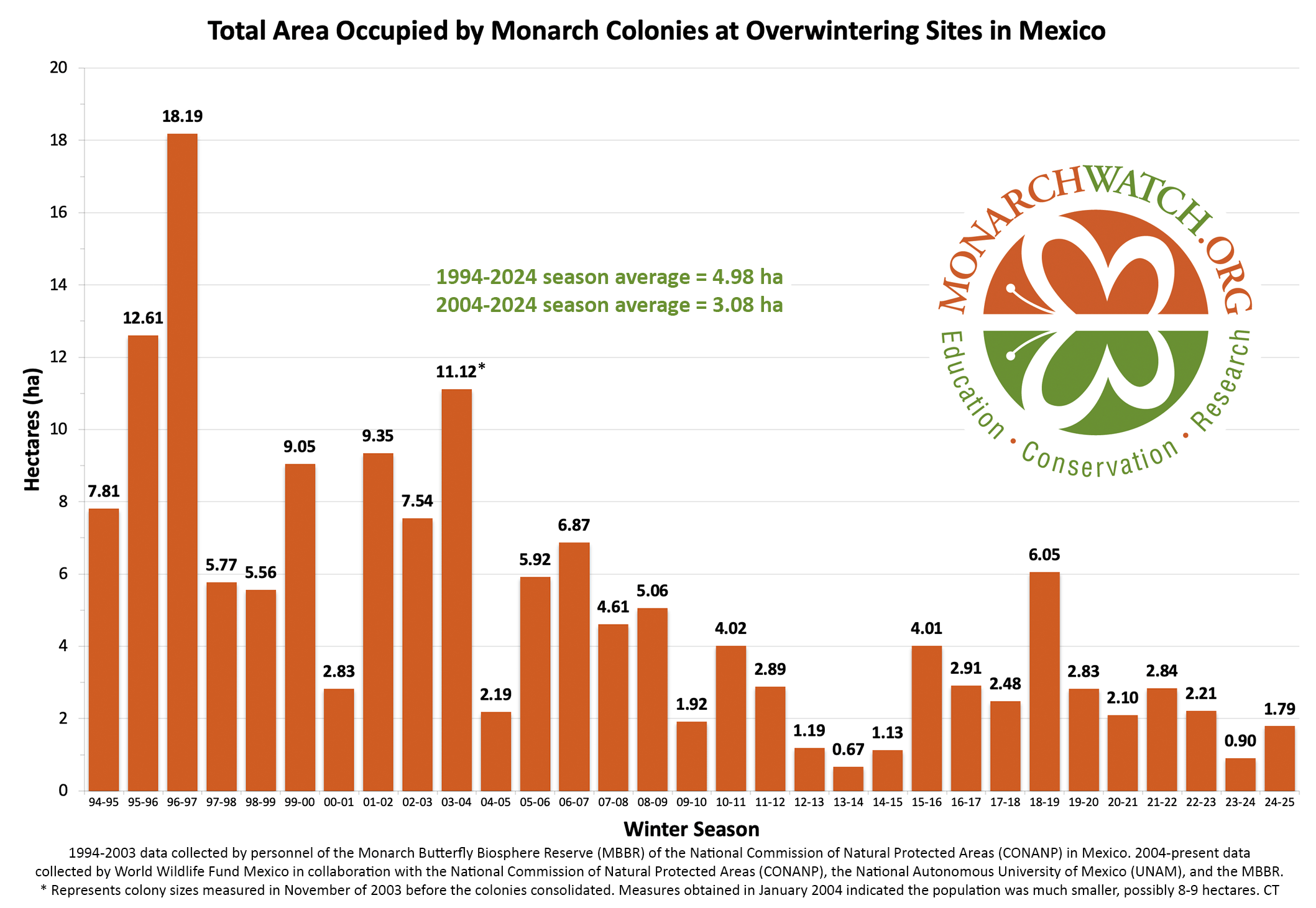

This is a bar graph from Monarch Watch showing the overwintering populations of eastern monarchs. 6 hectares are needed to have a sustainable population.

To say that this is a disappointment is an understatement. More than ever, monarchs need our help. Their populations have steadily declined and have been under stable repopulation numbers for the past few years. The Eastern population of monarchs (those in Iowa fall in this group) have declined by 80% since the 1990s. “According to the most recent monarch Species Status Assessment, by 2080 the probability of extinction for eastern monarchs ranges from 56 to 74% and the probability of extinction for western monarchs is greater than 95%.” (USFWS).