Updated on July 31

In an interview with KCCI, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds blamed the weather for high nitrate levels in the Raccoon and Des Moines rivers that led to an unprecedented outdoor watering ban for the Des Moines metro and dismissed any suggestion that Iowa needs to change its policies. Milli Vanilli’s 1989 hit “Blame it on the Rain” captures the vibe perfectly, so I covered the song and made a silly video with footage from the interview. However, the situation is no laughing matter.

Let me explain the situation as simply and clearly as I can. The high nitrate levels we are seeing this spring are not a fluke, drinking water is not completely safe in many communities across Iowa, and if we stay the course with Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy we will be waiting a long time for things to get better.

You can’t have it both ways

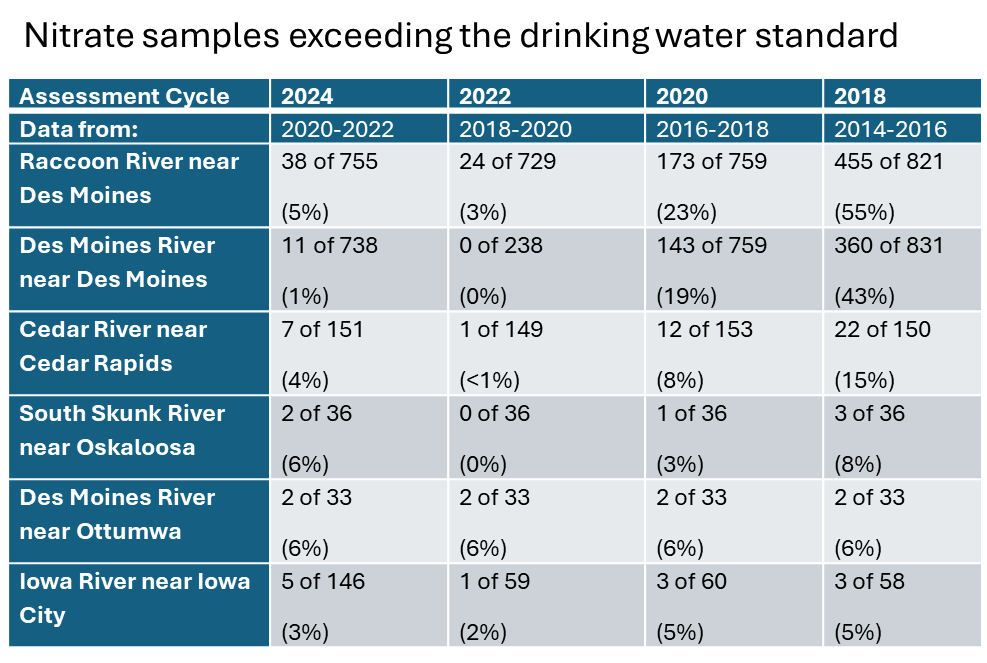

It’s true, nitrate pollution in rivers is influenced by both rainfall and recent drought. This has been a recurring theme in my analysis of water quality data (most recently here, and most rigorously here). But the Governor and her administration want to have it both ways. When nitrate in the Cedar River dropped due to favorable weather, they took that as a sign that a voluntary approach was working and took the unusual step of trying to withdraw a pollution budget that might have placed limits on new pollution from industry. Just last fall they were arguing that the following rivers should be removed from the Impaired Waters List, based on a 10% rule that makes no sense in the context of drinking water. The table below shows the data that they’re using to make those determinations.

Regardless of whether they meet the technical threshold for impairment, as a practical matter, the Raccoon River and Des Moines River regularly have nitrate levels high enough to cause problems for drinking water supply. The Central Iowa Water Works had to run their nitrate removal facility in 2024, 2022, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, and 2013. (This was reported recently by KCCI). It’s the largest such facility in the world, and this year it wasn’t enough!

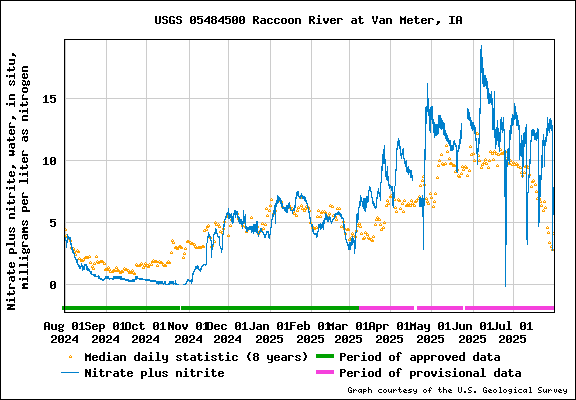

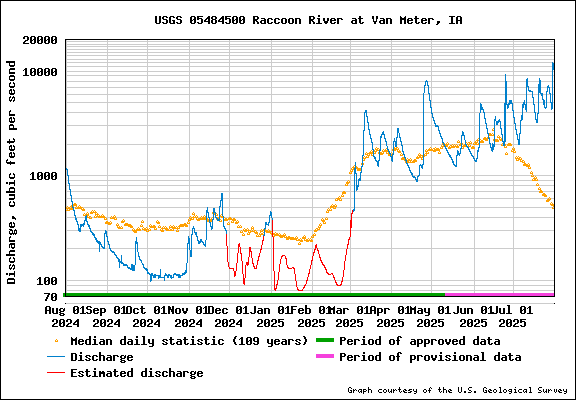

Nitrate levels this spring are higher than average but not a fluke

The graphs below shows how daily nitrate concentrations and discharge (streamflow) in the Raccoon River this year compares to the median for that time of year. It is unusual for wet weather and high nitrate levels to persist through late July, but nitrate does exceed 10 mg/L about half the time in May and June. If you want to understand long-term nitrate trends in the Des Moines River and Raccoon River, read Chapter 5 of the new source water report commissioned by Polk County.

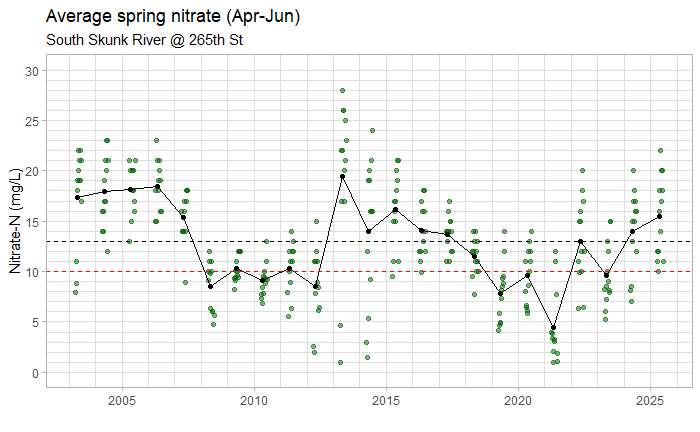

The Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers are not alone in having high nitrate levels this year. Here is 22 years of weekly data from a site on the South Skunk River, just downstream of Ames. This spring, peak nitrate levels (22 mg/L) were the highest we’ve seen since 2014. Average spring nitrate levels (15.5 mg/L) were the highest we’ve seen since 2015. However, it’s only a little above the long-term average (13 mg/L, indicated with a dotted black line) and ranks 7th out of 23 years for which we have data.

None of the data I’ve seen rules out a slight improvement in water quality in this or other Iowa rivers, masked by the ups and downs of an 8-10 year cycle. However the data does rule out this year being a fluke and us not having to worry about high nitrate levels in the future!

In Iowa, it’s normal for it to rain a lot in the spring. In watersheds with a lot of tile-drained farmland, it’s normal to see high nitrate levels for several days following a rainstorm. Ames is lucky to have a buried sand-and-gravel aquifer with the right geology and chemistry to remove most of the nitrogen before it reaches wells. If we withdrew water directly from the Skunk River, it would exceed the drinking water standard every year. Many other communities in Iowa are not as fortunate in their geology.

Nitrate in Drinking Water Poses a Widespread Health Risk

The Safe Drinking Water Act was written so that we must draw a hard line between “safe” and “unsafe.” Drinking water utilities must meet a Maximum Contaminant Limit of 10 mg/L nitrate as nitrogen. Most large water systems have been able to say on the “safe” side of the line, although it can be costly to do so. However, the standard hasn’t been updated to reflect research on the link between chronic exposure to nitrate in drinking water and various cancers. And really, it’s better to think of health risks as a continuum from “more safe” to “less safe.” The Environmental Working Group created a map a few years ago showing which communities fall in the “not as safe as they could be” range for nitrate in drinking water. Last year, Iowa Environmental Council recently released a report about the health risks of nitrate in drinking water and is now hosting a series of listening sessions on cancer and the environment.

Conservation efforts have been partially offset by increased fertilizer use

Shouldn’t we expect some improvement in nitrogen levels due to the state’s nutrient reduction strategy and the conservation efforts of farmers? I’ve written another article to dig into this question but the short answer is that we can expect at most a 2% reduction in nitrogen losses over the past decade. That’s for the state as a whole, some watersheds are doing better or worse and we don’t have a good tracking system to evaluate it. Most of the progress that we can expect from cover crops and nitrification inhibitors have been offset by increases in fertilizer application rates, which apparently made economic sense to do.

I can’t really blame farmers for acting in their economic self-interest. I do think it’s fair to blame your elected officials if they can’t take drinking water safety seriously and offer better solutions. Just don’t blame it on the rain.

Excellent essay. Great presentation on Monday’s zoom. I continue to work with Dan’s mutual friend, Charlie Bruner, on a variety of work, including Johnson Center for Land Stewardship Policy and GrassrootsIowaNetwork. Each of those efforts complement your work.