Trees for the Bees: How to Support Wildlife this Arbor Day!

These warmer days make it hard to sit still; we all want to get a jump on our yard and garden plans! Maybe you’re thinking of adding some small pockets of pollinator habitat. Or perhaps you’ve finally decided to add a tree or two for shade. While there’s a dizzying number of guides for “pollinator flowers”, there’s less advice on how homeowners can utilize trees and shrubs to support wildlife.

Planting a tree can be an investment not only of money but of time as well. When thinking about the long-term goals for your property, it’s important to think about the legacy you want to leave behind, as the tree may outlive you. Planting the right trees can not only increase your property’s appeal; it can also provide habitat for songbirds and pollinators for decades to come! So which trees are attractive to pollinators, are native to Iowa, and look great in our yards? We’ve put together a list to answer some of these questions, just in time for Arbor Day, which falls on April 28 this year!

But first: why trees?

Native trees and shrubs provide excellent wildlife habitat in several ways. Many provide an early flower source for pollinators such as bees and butterflies, and they are also great habitat for birds! Trees provide nesting and hiding areas for birds, and can attract insects that birds need to feed their chicks (more on that later). Planting native trees will especially invite butterflies and moths to visit your yard and lay their eggs, which hatch into caterpillars. These caterpillars then snack on tree and shrub leaves (they won’t do any real damage) until they spin their chrysalises or get plucked by a bird. Caterpillars and other insects are fundamental to the food web: they are the juicy, protein-filled link between plants and larger animals. If you want to see beautiful butterflies and songbirds, you should plant native trees that support native insects!

Native trees are central to an exciting, diverse yard!

The nonnative ginko tree (the one with fan-shaped leaves) supports about 4 species of caterpillars. In contrast, native oak trees alone can support 534 species of caterpillars (according to Dr. Doug Tallamy*). Consider the fact that black-capped chickadees need at least 300 caterpillars a day to feed their chicks – that’s about 5,000 caterpillars needed in a few weeks while the chicks grow! And this is just one example. Imagine if you had three chickadee families in your yard, or five other species of birds visiting your feeders. Suddenly, native trees just seem practical, and planting nonnative trees, such as a ginko, seems, as Tallamy put it, “equivalent to erecting a statue” in terms of its usefulness.

Unhelpful trees:

Let’s address the elephant in the room: some trees and shrubs commonly planted in yards are pretty damaging; they easily spread from our yards and choke out native plants that wildlife depend upon, and cost cities and counties thousands of dollars to remove from natural areas and building foundations (some of these trees’ roots can actually compromise the integrity of buildings). Some trees and shrubs to stay away from include: Bradford or Callery pear trees (Pyrus calleryana; also their flowers smell bad), Norway maples (Acer platanoides), buckthorn (Frangula species), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), and Amur and Morrow’s honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii and L. morrowii, respectfully).

Lastly, do your best to avoid planting cultivars and hybrids that promise better color, bigger flowers, etc. Most native trees (especially maples) produce spectacular fall color anyway, and the hybrids you see in the nurseries will likely be sterile, and won’t produce flowers that attract pollinators or birds (if they produce any at all). It is also important to note that nonnative shrubs, trees, and hybrids may tout that they produce berries, and therefore support wildlife. Birds in particular may feed on berries only certain times of the year, and that time may not coincide with berry production on hybrid plants. Additionally, these nonnative plants will not come close to supporting the number of caterpillars needed to keep birds nesting in or near your yard.

Now for the main event: the best shrubs and trees to plant!

How the lists are set up: Shrubs, small trees, and larger trees that are native to Iowa and beneficial to pollinators are listed below in order of bloom time. Each table describes a specific genus or species of tree, which is pictured to the right of the table (or below in mobile format).

Shrubs and small trees are listed first, and larger trees are listed afterwards. A small picture of the blooms produced by a shrub or tree may be displayed in the corner of the picture of the mature plant. These are not exhaustive lists; they are meant to get you started!

{ See end of article for a list of places to purchase native shrubs and trees! }

Shrubs

The following native plant species are shrubs and small trees reaching a maximum height of 30 feet. These trees are perfect for small yards, or large yards that want to add visual interest and diversity by planting trees of varying heights. Some of these shrubs also make great hedges or borders near property lines! Be sure to look up how some of these shrubs spread to make sure their maintenance needs meet your expecations.

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

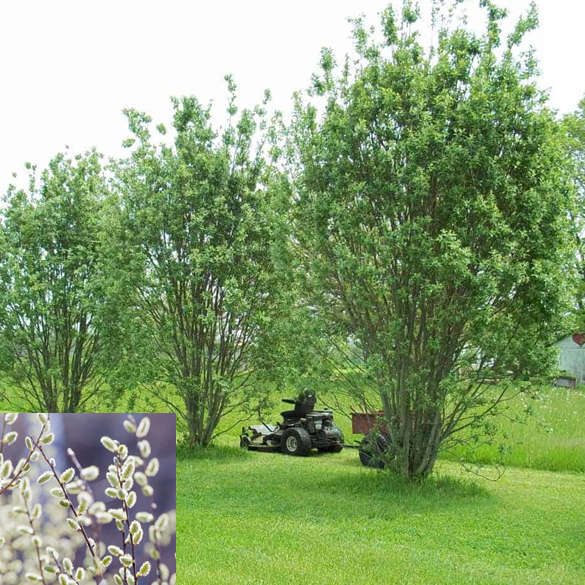

| Pussy Willow | Early to Mid-Spring | Full Sun, Wet – Moist |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Salix discolor | 2 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 6 – 20 ft | Small, fluffy white catkins | Dull green – yellow |

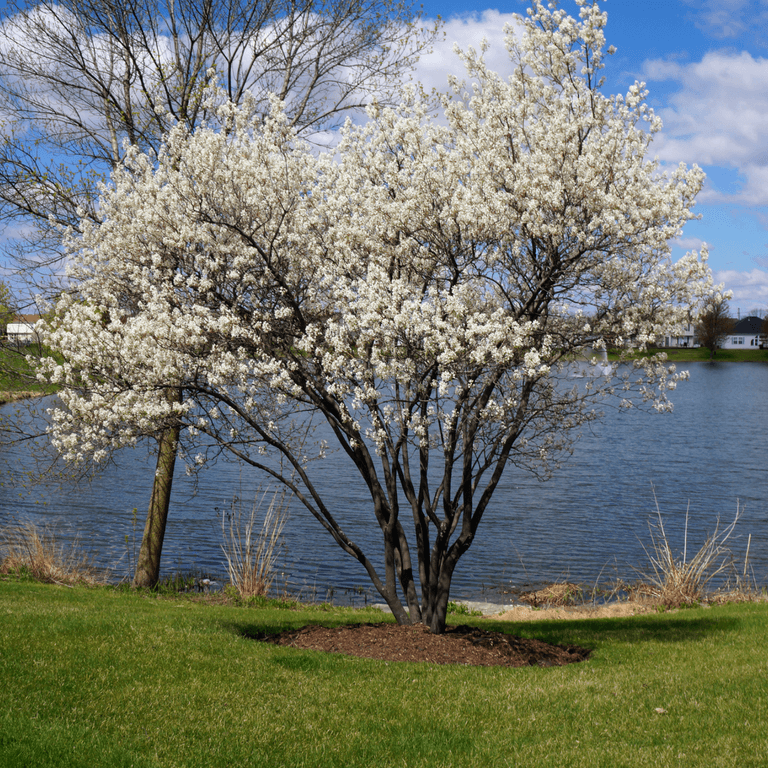

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Serviceberry (Juneberry) | Mid-Spring | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Dry |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Amelanchier arborea | 1 – 2 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds, and more |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 6 – 20 ft | White, 1-inch flowers | Red-orange |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Eastern Redbud | Mid-Spring | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Dry |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Cercis canadensis | 4 Weeks | Pollinators |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 15 – 25 ft | Showy pink flowers | Yellow |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| American Plum | Mid- to late Spring | Part – Full Sun, Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Prunus americana | 2 Weeks | Pollinators, Mammals |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 10 – 15 ft | Showy white flowers | Red to Yellow |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Prairie Crab Apple | Late Spring | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Malus ioensis | 1 – 2 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds, and more |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 10 – 25 ft | Showy white-pink flowers | Brown-orangeish |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Gray Dogwood | Late Spring to Mid-Summer | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Cornus racemosa | 3 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds, and more |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 8 – 15 ft | Showy white flowers | Red-purple |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| American Elderberry | Late Spring to Mid-Summer | Part – Full Sun, Moist |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Sambucus nigra canadensis, or Sambucus canadensis | 3 – 4 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 4 – 12 ft | Showy white flowers | Brown-reddish to Yellow |

Trees

The following species are taller native trees ranging from 40 to 120 feet tall. These trees will provide high-quality habitat in larger yards, and are sure to attract and support wildlife, especially if mutlitple species are planted. Be sure to check if these trees create any fruits or seed pods so you can determine which trees best match your expectations.

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Maples (Sugar, Black, and others) | Early to Late Spring | Part – Full Sun, Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Acer species | 1 – 2 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds, and more |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 60 – 100 ft | Small yellow-green flowers | Striking colors, varies by species |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Black Cherry | Late Spring to Early Summer | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Dry |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Prunus serotina | 2 – 3 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds, and more |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 50 – 80 ft | Showy white flowers | Yellow to reddish |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Kentucky Coffeetree | Late Spring to Early Summer | Part – Full Sun, Moist – Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Gymnocladus dioicus | 2 – 3 Weeks | Pollinators, Birds |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 60 – 90 ft | Small white flowers | Yellow |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Basswood (Linden) | Early Summer | Part – Full Sun, Medium |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Tilia americana | 2 Weeks | Pollinators |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 50 – 100 ft | Small white flowers | Dull green – yellow |

| Common Name | Bloom Period | Sun and Soil Needs |

| Oaks (Red, White, and others) | Varies | Varies |

| Species Name | Bloom Length | Wildlife Supported |

| Quercus species | Varies | Invaluable to countless wildlife |

| Max Height | Bloom Description | Fall Color |

| 40 – 80 ft | Varies | Dull to striking colors |

* = According to research by Dr. Doug Tallamy, author and faculty member at the University of Delaware.\

This article used a number of resources, including:

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center Michigan Department of Natural Resources

Missouri Botanical Garden Michigan State University

University of Minnesota Extension USDA NRCS PLANTS Database

Some great native shrub and tree nurseries:

The State Forest Nursery: Ames, Iowa. 1-800-865-2477 or 515-233-1161

Iowa Native Trees and Shrubs: Woodward, Iowa. 515-664-8633

Blooming Prairie Nursery: Carlisle, Iowa. 515-689-9444