Drainage “Improvements”

Sometimes, cutting down trees and moving earth along a stream is necessary to ensure adequate drainage for crops or prevent destructive flooding. Sometimes, it is necessary to reconnect a stream with its floodplain after centuries of hydrologic alteration, erosion and siltation. Sometimes cutting down trees and moving earth isn’t necessary at all, or could be done in a much smaller footprint. You can’t always tell which is which unless someone who knows the land goes to the trouble of reading dull engineering reports and attending dull meetings.

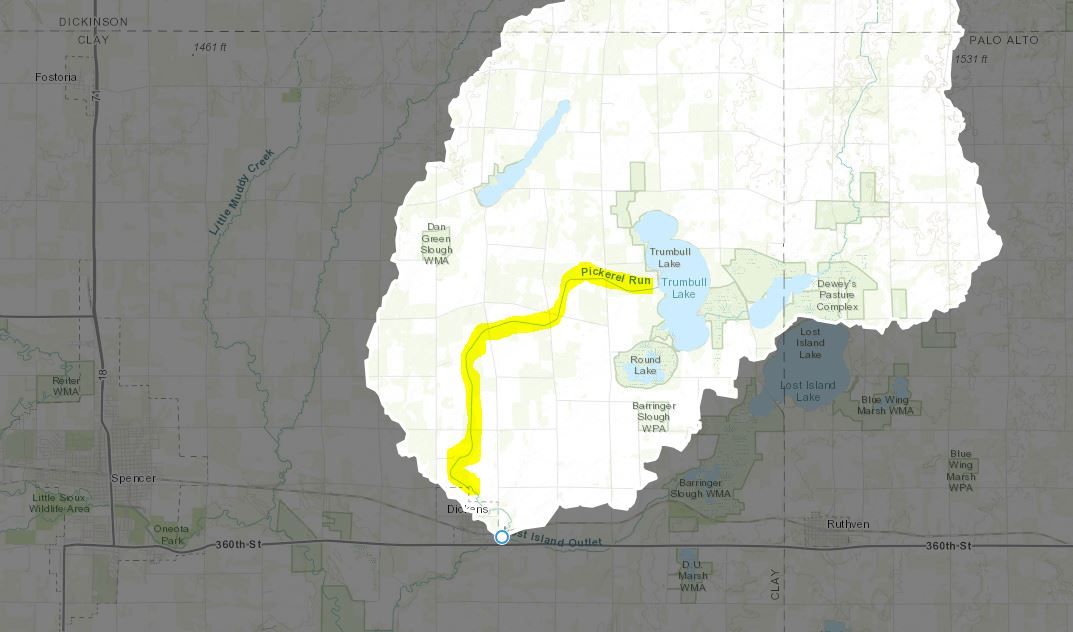

In 2020, a group of landowners successfully petitioned to reclaim trusteeship of their drainage district from the Clay County Board of Supervisors in order to block what they see as a “huge, costly, and environmentally destructive improvement on Pickerel Run.” I share this story, related by Steve Swan, in hopes it encourages more people to go to the trouble.

-Dan

By Steve Swan

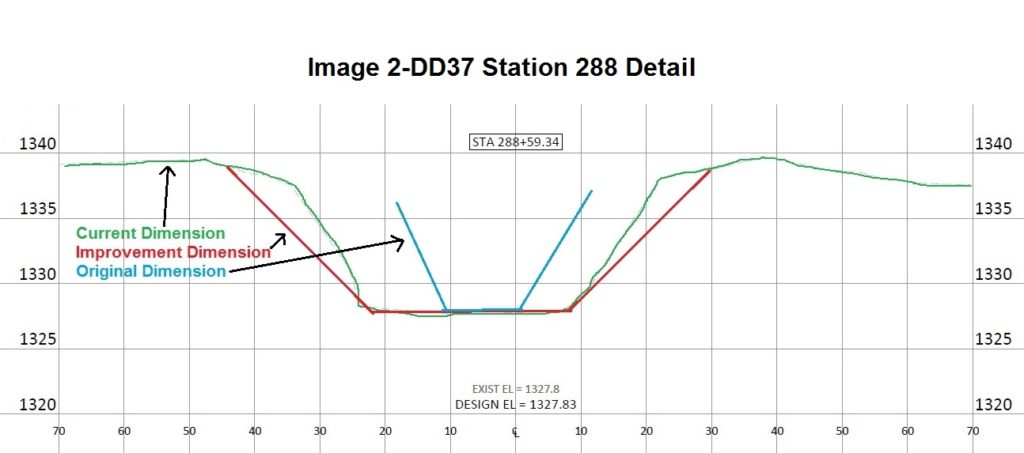

Pickerel Run is a tributary of the Little Sioux River, located east of Spencer. Drainage District #37 was formed in 1917 to improve drainage by dredging, straightening and widening parts of this stream. Pickerel Run is unusual in that it has not silted in and in many places is almost twice as wide as originally constructed, and therefore is capable of carrying more water than the original design. These days, fewer farmers are grazing livestock and trees have grown up along the banks. Trees can impede drainage when they fall into the channel or when they grow too close to the normal waterline, so some need to be removed, but most are not causing problems and seem to be stabilizing the bank.

Our understanding of the situation was not reflected in the 2018 report by Bolton & Menk, which took several years to complete and cost over $100,000. Landowners were oblivious to what was going on until the report was done and a $3.6 million improvement was recommended, which would remove all trees within a 300-foot work area, level the spoil banks, and dredge the stream. The engineers were sure that 55,000 acres of land upstream could be annexed once the project was completed and be made to pay a significant portion of the bill. This proposal came at a time when cash rents in Clay County had been falling for several years.

In many counties, the county supervisors act as trustees for the drainage districts. Iowa code is clear that trustees are obligated to make repairs if necessary, desirable and feasible. However, Iowa’s drainage laws (Section 468) make easy for engineering firms to initiate a massive drainage project—a single signature on a petition—and very difficult for the landowners who must ultimately pay for the project to stop it once it gets rolling. The remonstrance process requires representation of 70% of the acres and 50% of the owners to vote against the project, with parcels held the government or still in the name of a deceased owner defaulting to count in favor of the project.

Once they found out what was happening, landowners began the remonstrance process, and were assured that time would be given for owners to register their opposition of the project. The supervisors called the remonstrance vote early and an initial reading of the results showed a shortfall of the votes needed to stop the project, but the spreadsheet used to calculate the remonstrance contained many errors. A lawsuit ensued.

Realizing that the supervisors were going to stay their course, landowners took advantage of the law and forced a vote to make the trusteeship of the drainage district private. There were more irregularities and another lawsuit for which our landowners had to pay both sides.

Eventually landowners won control of Pickerel Run/DD#37. After the successful privatization of our district, the “drainage industry” successfully lobbied for an amendment to Iowa Code 468 making it more difficult for other districts to follow suit.

Since the landowner trustees have taken office, a plan has been developed to keep water flowing while still maintaining some of the wonderful habitat that had developed over the past 100 years. Some trees have been cut, but many have been saved. Money is being spent, but much less than what would have been spent. The bed of the creek, which supports five species of native mussels and seventeen species of fish, has been spared a clean sweep by big earth moving equipment. The banks are still a haven to a multitude of wildlife species, including a great blue heron rookery, bald eagles, countless waterfowl, and deer in a sea of corn and soybean fields.

Iowa is a farm state and water does need to drain. Perhaps the simplest and best way to ensure that drainage projects are only done when truly needed would be to amend the threshold required for a remonstrance to stop a project.

My dream would be that all the groups that support quality of life in Iowa would become aware how important Iowa Code Section 468 is to life in Iowa and come together to lobby and oppose self-serving engineering firms in the drainage industry that are mainly looking for additional projects to generate revenue, regardless of damage done.