End the No Swim Era

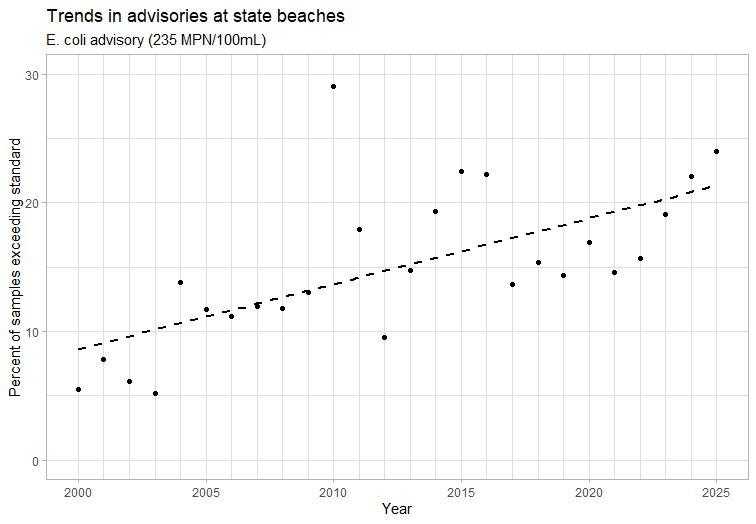

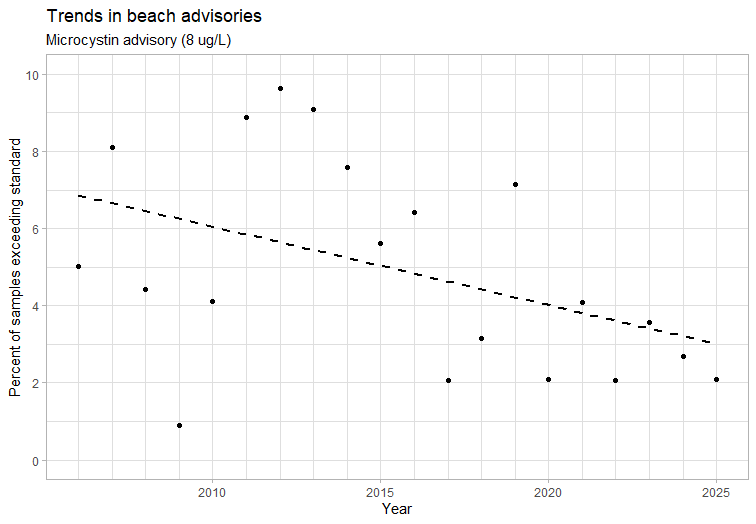

The Driftless Water Defenders launched a social media campaign last summer calling for the end of Iowa’s #NoSwimEra. It’s a catchy slogan, and timely. 2025 was an especially bad year for recreational water quality. The Iowa DNR tests for E. coli (an indicator of poop in the water) and microcystin (a toxin produced by algae) at 41 beaches at state parks, every week between Memorial Day and Labor Day. If you had picked a beach and weekend at random for a family outing, there is a 1 in 4 chance you would have encountered a “Swimming Not Recommended” sign when you got there. Over the past 25 years, the number of microcystin advisories has fallen but the number of E. coli advisories and the number of beaches affected has increased.

Iowa’s water quality problems aren’t unique, but they are a lot worse than some of our neighbors. I analyzed 2025 E. coli data from Wisconsin beaches and found that 11% of the water samples had high enough E. coli levels to trigger an advisory (235 CFU/100mL), versus 24% in Iowa. 3% of Wisconsin beaches had average E. coli levels high enough to violate water quality standards (a seasonal geometric mean of at least 126 CFU/100mL), versus 25% of Iowa beaches.

Some of the advisories are posted at lakes where there has already been a lot of public funding invested in lake restoration and in voluntary soil conservation projects in the watershed, so don’t think we can solve this problem with more of the same. At Lake Darling, the work seems to have been undone by an expansion of the hog industry. At the Lake of Three Fires, the work seems to have been undone by conversion of pasture to cropland, motivated by the Renewable Fuel Standard. We need to take a hard look at how state and federal policies allow or even encourage farming practices that foul our lakes.

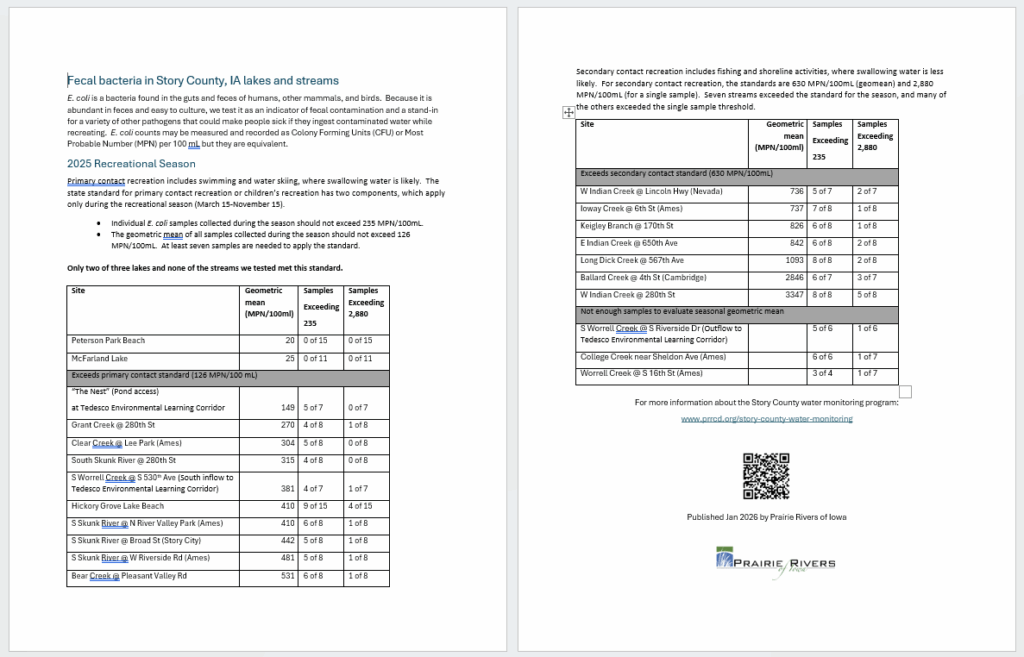

However, I follow the data where it leads, and it doesn’t always lead to a hog barn. Here is my latest summary of E. coli data collected by the water monitoring program in Story County. Hickory Grove Lake has been well-studied by the DNR, and both DNA markers and transects point to Canada geese on the beach, not livestock in the watershed. College Creek is usually our worst stream on days when it’s flowing, and it has an urban watershed. A large fraction of the bacteria in West Indian Creek came from an old sewage treatment plant that was just replaced this year. DNA testing of water from Ioway Creek showed that human waste is present. We’ll be doing more testing in 2026 to confirm this and narrow down the sources, including a volunteer event in early summer. Donations also help support our monitoring and education efforts!

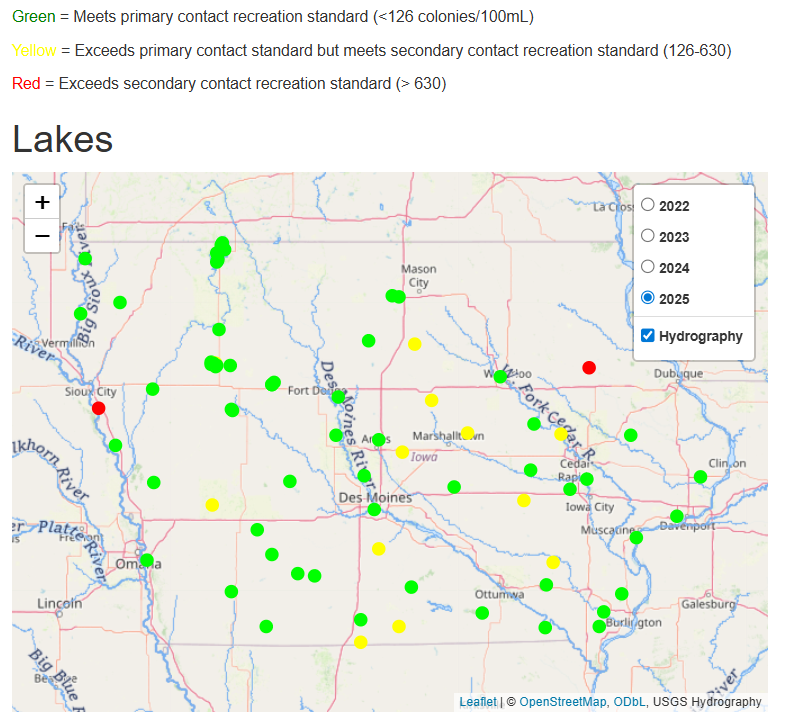

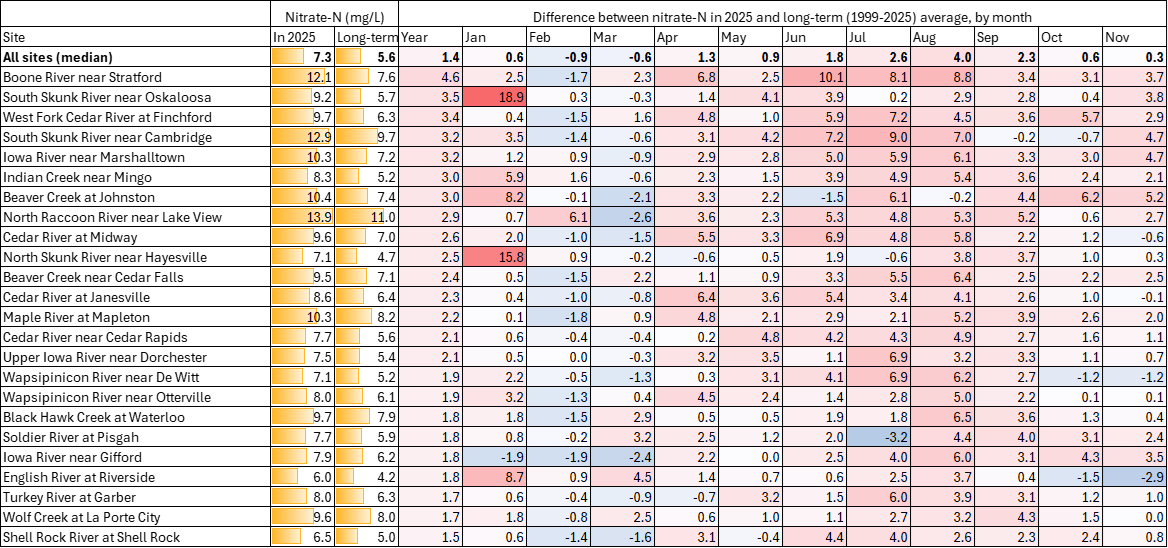

Some people are afraid to dip a toe in any lake or river in Iowa, and their No Swim Era goes back decades. That’s a shame. Even in a bad year, it’s possible to find clean water for recreation. For example, I took my daughter and her friend swimming and paddleboarding at Peterson Park, a Story County-owned beach where E. coli counts never exceeded the double digits. I joined Iowa Project A.W.A.R.E. to canoe and clean up trash on some scenic stretches of the Upper Cedar and Shell Rock Rivers, which averaged 69 and 45 CFU/100mL for the season–the standard is 126. I’ve updated this interactive map to help you find others.

The new Currents of Change report has some good tips for minimizing your risk of a waterborne illness when recreating in waters of poor or unknown quality. I regularly go in Ioway Creek, which I know to have poor water quality, but pack hand sanitizer and do my best to keep my head above water. I dunked my head in the Winnebago River (which was muddy and hadn’t been tested recently) multiple times during a whitewater kayaking class, but wore nose clips. I stay out of green water but otherwise am comfortable with a certain amount of risk to be able to enjoy the outdoors. But that’s just making the best of a bad situation. No Swim advisories have gotten way too common, and we need to work together to clean up our water and end that era!