Revised December 10

It sounds too good to be true, wrote Neil Hamilton in a 2021 opinion piece. Reducing nitrogen fertilizer application rates to the Maximum Return to Nitrogen (MRTN) recommended by Iowa State University promised to save farmers money while keeping nitrate out of the rivers and greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere. In retrospect, it was too good to be true.

Reducing fertilizer rates will cut into profits (for most farmers)

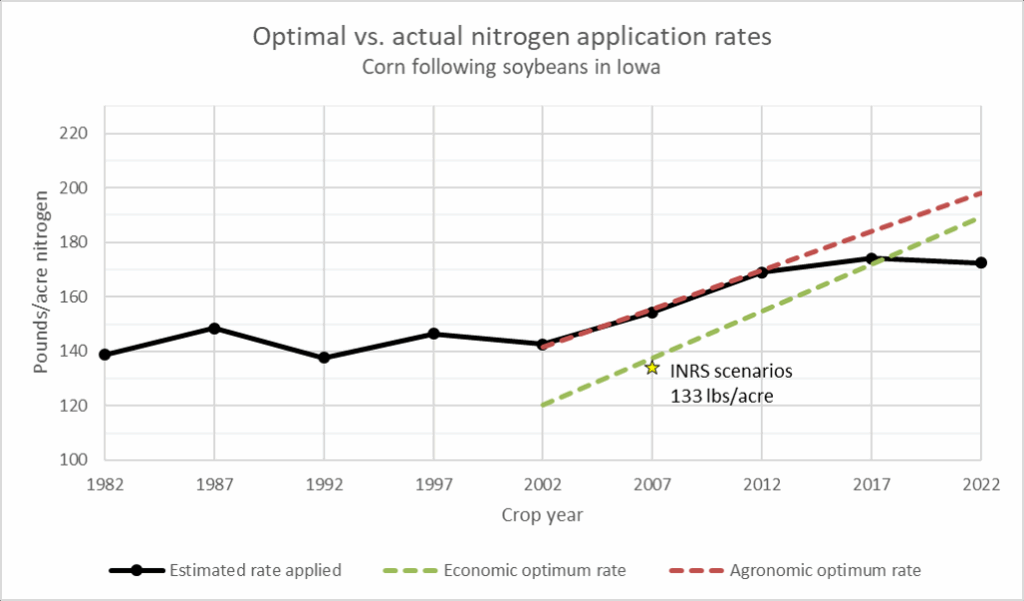

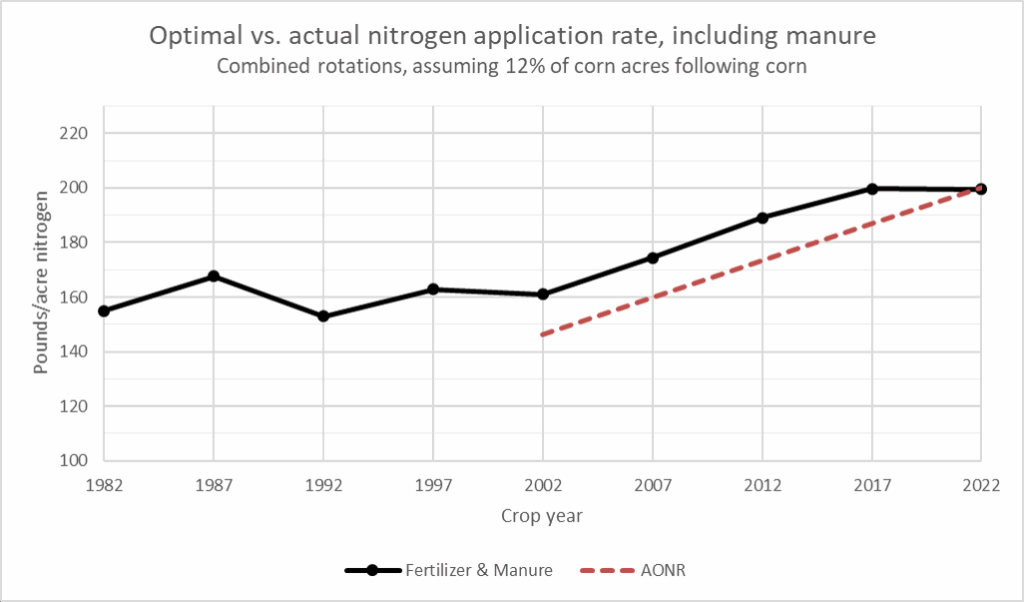

Early this year, ISU researchers published a study in Nature Communications showing that the amount of nitrogen fertilizer required to maximize yield (the agronomic optimum) and maximize profits (the economic optimum) have been steadily increasing, driven partly by corn genetics and partly by weather. The economic optimum is always lower than the agronomic optimum (the revenue from those last few bushels isn’t enough to pay for the fertilizer) but the difference between the two is getting smaller. I wrote about this in July, but since then I’ve had a chance to download and explore the data used in the study. Here are the trends in optimal nitrogen application rates for just the sites in Iowa, compared to actual nitrogen application rates, which I estimated using a combination on IDALS fertilizer sales data and INREC survey data. For more details on the data I used to estimate actual nitrogen application, read this attachment.

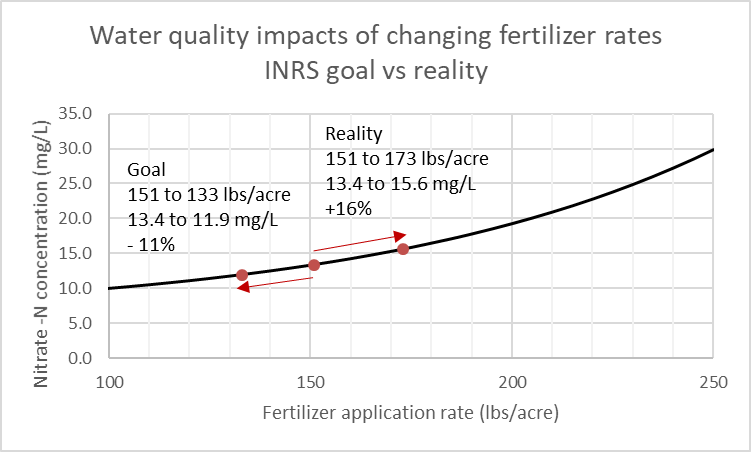

The scenarios in the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy were based on data from 2006-2010. At that time, it would have been possible for farmers to reduce nitrogen application rates on corn following soybeans from 151 lbs/acre to 133 lbs/acre while increasing profits, on average. However, those figures were already out of date when the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy was released in 2013, and in the decade since, fertilizer application rates have levelled off while the amount of nitrogen needed to maximize yields or profit has continued to increase. A minority of farmers may still find opportunities to boost profits by reducing nitrogen application, but average rates are now below the economic optimum.

This part of the study looks solid and matches what I’ve seen from other sources. Practical Farmers of Iowa have done their own trials and found that a majority of their participants were able to save money by reducing nitrogen rates in an especially dry year, but in a more typical year only 41% of farmers saw potential for savings.

Reducing fertilizer rates could still have significant water quality benefits

Farmers no longer have an economic incentive to reduce rates (on average) but it’s not hard to imagine policies that could shift the incentives by making it cheaper or less risky to apply at low rates, or more expensive to apply at high rates.

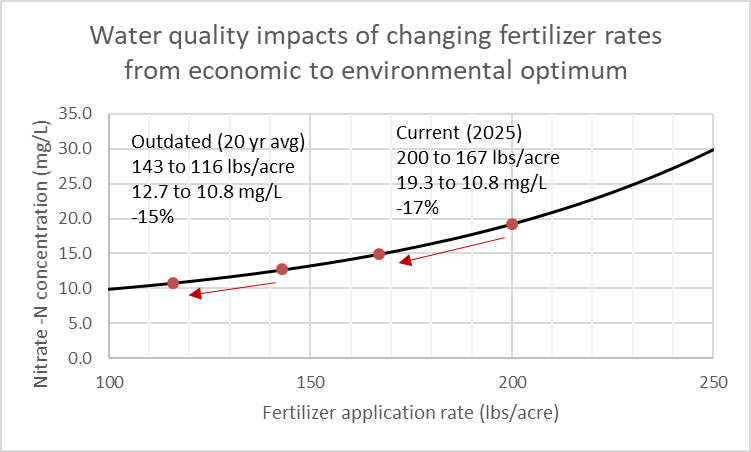

The ISU study includes an “environmental optimum nitrogen rate” that hints at that. The authors used a crop systems model to estimate nitrous oxide emissions and nitrate leaching for different scenarios, assigned a price to the pollution, and calculated the nitrogen application rate that would be economically optimal if those costs were reflected in the marketplace. Instead of evaluating the environmental benefits of reducing rates from current levels, they estimate the impacts of reducing rates (for corn after soybeans) from an economic optimum of 143 lbs/acre to an environmental optimum of 116 lbs/acre. Those are averages for the entire 20 year period and not at all relevant today. Oops! Because of this mistake, they conclude that “a reduction in N fertilizer rate towards improving sustainability will not have the anticipated reduction in environmental N losses because of the nonlinear relationship between N rate and N loss.”

Actually, the non-linear (curved) relationship between nitrogen application rates and nitrate pollution implies that rate reduction will have bigger benefits now than it did when rates were lower. The figures below contrast some outdated assumptions with new reality.

The increase in fertilizer rates has been bad for water quality

In most presentations and interviews about the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, ISU faculty correctly point out that fertilizer management alone is not enough to meet our water quality goals and emphasize the need for a variety of conservation practices. However, every scenario in the INRS assumed that fertilizer application rates would go down. It may not be possible to meet our goals now that fertilizer rates have gone up.

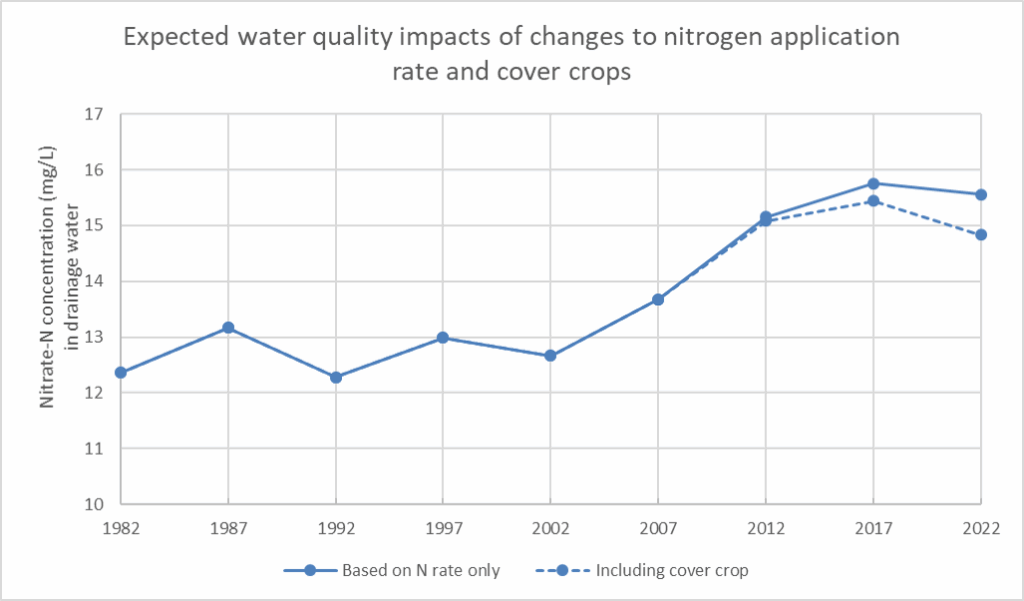

Based on the increase in fertilizer rates for corn after soybeans (from 151 lbs/acre in 2007 to 173 lbs/acre since 2017), we would expect a 16% increase in nitrate concentration in drainage water. The 3.8 million acres of cover crops reported in recent INREC aren’t enough to undo the damage. Nitrate in streams is also affected by weather, changes in land use, and other practices not modeled here, but fertilizer rates and cover crops do help to explain why nitrate concentrations in many streams peaked between 2013 and 2015 and have fallen since.

What about continuous corn?

Nitrogen application rates for corn after soybeans have gone up, but application rates for continuous corn may actually have gone down. I say “may” because we didn’t have good baseline data. Because corn stover ties up a lot of nitrogen as it decomposes, growing corn after corn requires higher nitrogen application rates to achieve the same yield. The confusing Figure 5 in the Nature Communications paper looks at the yield penalty for reducing nitrogen rates from the economic optimum to the “environmental optimum,” which is what it would make economic sense for farmers to apply if the societal costs of pollution were reflected in the marketplace. The authors concluded that reducing nitrogen application rates past the economic optimum would have unacceptable consequences for grain markets and food security, especially for continuous corn. I looked at the same figure and concluded that growing corn after corn would not be commercially viable in a society that valued clean water, a stable climate, and public health.

Your mileage may vary

My biggest takeaways from both the Iowa State University research and the Practical Farmers of Iowa research are how much the optimum nitrogen rate varies from year to year and place to place. One farmer in the PFI study saved money by reducing rates from 150 to 100 lbs/acre, while another lost money by reducing rates to 246 to 200 lbs/acre.

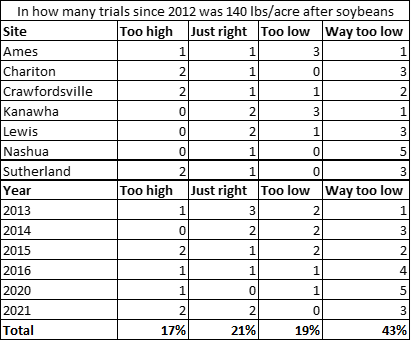

The ISU study includes nitrogen rate trials for seven sites in Iowa and six years since the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy was released. If you had followed the recommendations from the old nitrogen rate calculator and applied 140 lbs/acre to corn after soybeans, 62% of the trials would been at least 10 lbs/acre below the economic optimum. But even in the most recent year, there were 2 sites where that would have been at least 10 lbs/acre above the economic optimum!

The Iowa Nitrogen Initiative addresses this problem through an expanded program of nitrogen rate trials and a decision support tool that can provide customized recommendations by county given assumptions about rainfall, planting date, and residual soil nitrate. Using the new information, some farmers will find an opportunity to increase profits while reducing nitrogen rates. A larger group of farmers will find opportunities to increase profits by increasing nitrogen rates. Dr. Castellano has made a complicated argument for how the water quality benefits of bringing down the high rates can be greater than the water quality penalties of bringing up the low rates. Great. Please apply that logic to manure.

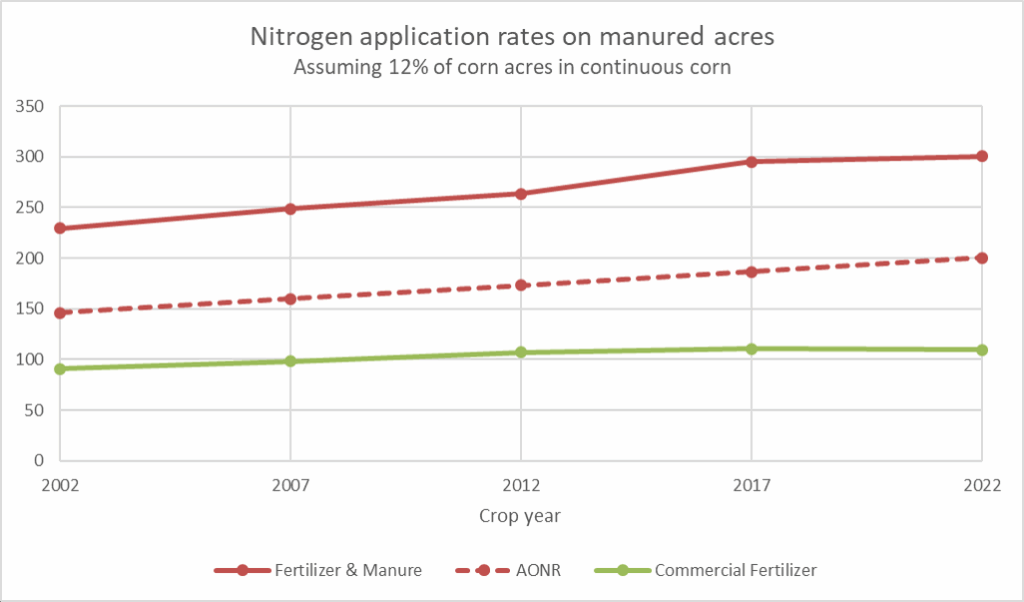

What about manure?

Since 2017, the INREC survey report has asked farmers what percent of fields receive manure application (about 20%), how much commercial fertilizer is applied to fields that do not (174 lbs/acre for corn in rotation and 199 lbs/acre for continuous corn), and what proportion of cropland is planted to continuous corn (about 12%). Manure expert Dan Anderson recently did some algebra to see what that implies about nitrogen application rates for fields that do receive manure, and came up with 342 lb N/acre on corn-after-soybean and 391 lb N/acre on continuous corn. I used slightly different assumptions and came up with lower numbers, but they’re still much higher than needed to maximize yield. If you’ve read anything by Chris Jones, this won’t come as a surprise.

I’m showing the agronomic optimum rate rather than economic optimum because the economics of manure aren’t the same as commercial fertilizer. Manure has much lower nutrient content and is much more expensive to haul. Manure pits fill up and there’s often a time and labor crunch to get it applied. Manure has highly variable nutrient content, which adds to the uncertainty and makes a supplemental application of commercial fertilizer seem like cheap insurance. If farmers had a strong economic incentive to make the most of manure nitrogen, nobody would be applying it in early fall and we wouldn’t have a cloud of ammonia hanging over the Midwest. There are also some farmers who are doing an exceptional job of conserving soil and water by feeding cover crops, small grains, or forage to livestock, and we should figure out how to level the playing field to make it easier to replicate their model.

Are these changes in nitrogen management good or bad?

It’s a mixed bag. I had to puzzle over this for quite a while!

The increase in the economic optimum nitrogen rate is partly due to good things (improved corn yield response) and partly due to bad things (increasing nitrogen losses to the air and water).

It’s good that nitrogen fertilizer use has gotten more efficient. Farmers can grow more bushels per pound of nitrogen than they used to. It’s bad that manure management plans still allow nitrogen to be applied at a rate of 1.2 lbs per bushel of potential yield.

It’s good that fertilizer rates for corn following soybeans have levelled off recently. It’s bad that nitrogen fertilizer rates went up in the early 2000s.

It’s good that nitrogen application rates for continuous corn have fallen. It’s bad that farmers are planting corn after corn.

It’s good that farmers are now applying less commercial fertilizer (on average) than required to maximize yield. It’s bad that farmers are over-applying manure.

It’s bad that we don’t have a plan to reach the goals of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy without rate reduction, and it’s bad that the price tag of reducing rates (either to farmers, the public, or both) is higher than we previously assumed. However, it might still be a better deal than other conservation practices. It’s bad than more people aren’t talking about this.