Raccoon River Valley Trailhead in Jefferson Honors History and the Lincoln Highway

Coming from the east along the Lincoln Highway through the town of Jefferson, there is a location where the car seems to be drawn to a stop and the traveler is compelled to get out and explore. On the north side of the road is a beautiful, landscaped area with plants and sculptures while on the south side there is the restored and welcoming Milwaukee Railroad Depot (along with the county Freedom Rock!). Both sides of the road are part of the Raccoon River Valley Trail (RRVT) trailhead.

The Railroad Years

The Chicago & North Western Railroad brought the railroad tracks to town in 1866, and by 1906 the Milwaukee and St Paul routes ran through Jefferson as well connecting Des Moines and the Iowa Great Lakes Region. Replacing smaller versions of a depot, the current depot was built from a standard Milwaukee plan between 1906 and 1909. There was once a cast iron horse trough that was attached to the building. Because Jefferson was the county seat of Greene County, the depot here was larger than most with two waiting rooms, indoor plumbing, and an express and baggage room. Greater ornamentation was also given to the structure.

The Lincoln Highway Cruises In

The Lincoln Highway Cruises In

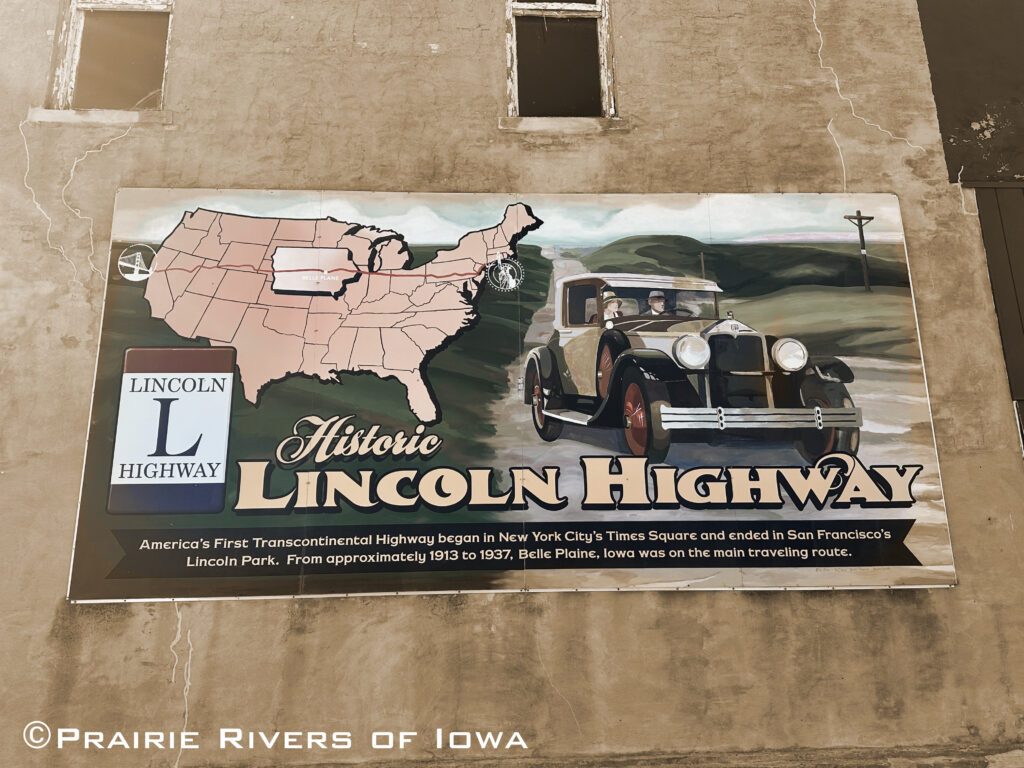

By 1913, the Lincoln Highway was proposed and its paving across Greene County came soon afterward from local and city funding. The city square was just a few blocks west of the Milwaukee Depot, and in 1918 a grand Classical Revival style building made of limestone was built to replace the brick county courthouse. In that same year, resident E.B. Wilson donated a statue of Abraham Lincoln to honor the Lincoln Highway and the new courthouse. This new ease and popularity of automobile travel became the preferred way to get from place to place. By 1952 the passenger service on the Milwaukee RR was discontinued. By the middle of the 1980s freight service ceased operation as well.

A New Use

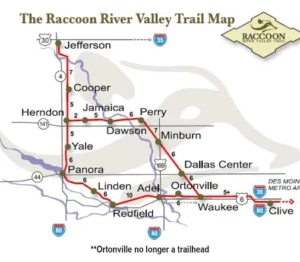

It was time for a new use for the old railroad right-of-way. Through a vision of the Iowa Trails Council and the Conservation Boards from Dallas and Guthrie counties, the Raccoon River Valley multi-use Trail (RRVT) was born in 1987, with the first paved trail in 1989. The 12-mile addition from Jefferson to the south was completed in 1997 after Greene County joined the group. Today, the trail is an 89-mile paved surface running from Jefferson to Waukee, with plans to connect to the High Trestle Trail by the end of 2024.

One of the goals of the Raccoon River Valley Trail Association was to keep the history alive in the towns along the trail and to give new life to the communities. There are signs noting historical points of significance along the entire route, several restored or remaining train depots, and signs that remain from the railroad days.

The Jefferson Trailhead

The addition of the Milwaukee Depot Trailhead in Jefferson has been significant to telling the story of the Lincoln Highway. Thousands of bicyclists, joggers, walkers, skaters, campers, cross-country skiers, birdwatchers, hunters, fishermen and naturalists from all across the state are drawn to the Raccoon River Valley Trail. The Lincoln Highway interpretive signs at the trailhead are only the beginning to how Jefferson tells the Lincoln Highway history.

Jefferson and the Lincoln Highway

Adjacent to the Raccoon River Valley Trail is the Greene County Freedom Rock, the 53rd in the state, and completed in 2016. The Lincoln Highway is one of four subjects painted on the rock. In the Greene County News, October 28, 2016, artist Bubba Sorensen states that the rocks are to thank veterans for their service and to tell the unique stories of each county. The Lincoln Highway scene depicts the 1919 U.S. Army motor transport corps convoy across the Lincoln Highway and then LTC Dwight D. Eisenhower looking toward the convoy.

Approximately one block to the west of the RRVT is the Deep Rock Gas Station. Built in 1923, the building was in use until the 1990s. The site was given to the city in 2007. Using federal EPA “brownfield” funds, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources removed the station’s seven underground tanks. Using other grants and fund sources the station was restored and rededicated in 2014. An interpretive sign is located at the station to provide more insight on the historic Lincoln Highway.

A few blocks farther to the west is the Greene County Museum and Historical Center housing Lincoln Highway memorabilia. A sidewalk painting of the Lincoln Highway roadway leads from the museum to the Thomas Jefferson Gardens and ends at the town square. An interpretive sign along the sidewalks speaks of the Lincoln Highway.

At the center of the town square is the Greene County Courthouse, the Abraham Lincoln Statue, a 1928 Lincoln Highway Marker, and the Mahanay Memorial Carillion Tower. The tower allows for elevator rides to a 128-foot-high observation deck with views to rooftop art, to the surrounding counties and to… the Lincoln Highway.

At the center of the town square is the Greene County Courthouse, the Abraham Lincoln Statue, a 1928 Lincoln Highway Marker, and the Mahanay Memorial Carillion Tower. The tower allows for elevator rides to a 128-foot-high observation deck with views to rooftop art, to the surrounding counties and to… the Lincoln Highway.

The Raccoon River Valley Trail is nationally recognized as an exceptional rails-to-trails conversion and was a 2021 inductee into the rail-trail Hall of Fame. It has the longest paved loop trail in the nation and connects 14 Iowa communities with a unique outdoor recreational experience. Visit their website to plan your next railroad biking adventure and to support the communities built along railroad and Lincoln Highway history!

The Raccoon River Valley Trail is nationally recognized as an exceptional rails-to-trails conversion and was a 2021 inductee into the rail-trail Hall of Fame. It has the longest paved loop trail in the nation and connects 14 Iowa communities with a unique outdoor recreational experience. Visit their website to plan your next railroad biking adventure and to support the communities built along railroad and Lincoln Highway history!