The Legacy of the IOWATER Program

For 18 years, staff with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources trained and equipped volunteers to test water quality in rivers and streams across the state, building a network of citizen scientists and conservation leaders in the process. The IOWATER program died in 2016 after a long battle with budget cuts, declining participation, and IT challenges. It is survived by the state’s largest river cleanup event (Iowa Project A.W.A.R.E.) and many volunteers who resumed or started monitoring with the support of the Izaak Walton League, county conservation departments, watershed coalitions, and local non-profits.

The first Iowa Water Summit in 2019 was a sort of a funeral for the IOWATER program and a passing of the torch to the Izaak Walton League’s Save Our Streams program. Several groups in Iowa are making good use of the Ikes’ online database, trainers and training materials, and extra supplies. However, stream monitoring in the post-IOWATER era is decentralized and locally-led. Prairie Rivers of Iowa thought we could all benefit from more collaboration, so we wrote a grant proposal that was funded by the Water Foundation. Over the past year, I’ve been meeting regularly with colleagues from the Iowa Environmental Council, Northeast Iowa RC&D, Pathfinders RC&D, Partners of Scott County Watersheds, Polk County Conservation, and Drake University to talk about water monitoring, lay the groundwork for some new tools, and help the Izaak Walton League plan a second Water Summit.

The second Iowa Water Summit (scheduled for Oct 8 in Des Moines) is an opportunity for anyone involved in a local monitoring program (or looking to start one) to come together and learn from the experience of others around the state. We’ll have time and space for displays and networking. We’ll have a panel about recruiting and retaining volunteers. We’ll have a talk about making sense of the data once you have it, and another about new methods like microbial source tracking. We’ll have a panel about communicating with the public and turning data into action. If you’re at all interested in water quality and water monitoring in Iowa, don’t be shy! Register before September 20!

The other legacy of IOWATER is less trash in our rivers. Iowa Project A.W.A.R.E. was started in 2003 by IOWATER coordinator Brian Soenen, who now serves on the board of a non-profit that continues the tradition. This year, 269 volunteers in canoes removed and recycled 3.8 tons of trash from 60.2 miles of the Skunk River.

This was my first year participating in the cleanup and I highly recommend it! In addition to the fun of being on the water and the satisfaction of leaving the river cleaner than you found it, I enjoyed good food, friendly people, and interesting evening nature programs, including live turtles and a dugout canoe!

A.W.A.R.E. stands for A Watershed Awareness River Experience, and I tried to raise some watershed awareness in my Monday afternoon talk about the hydrology and water quality of the Skunk River. For example:

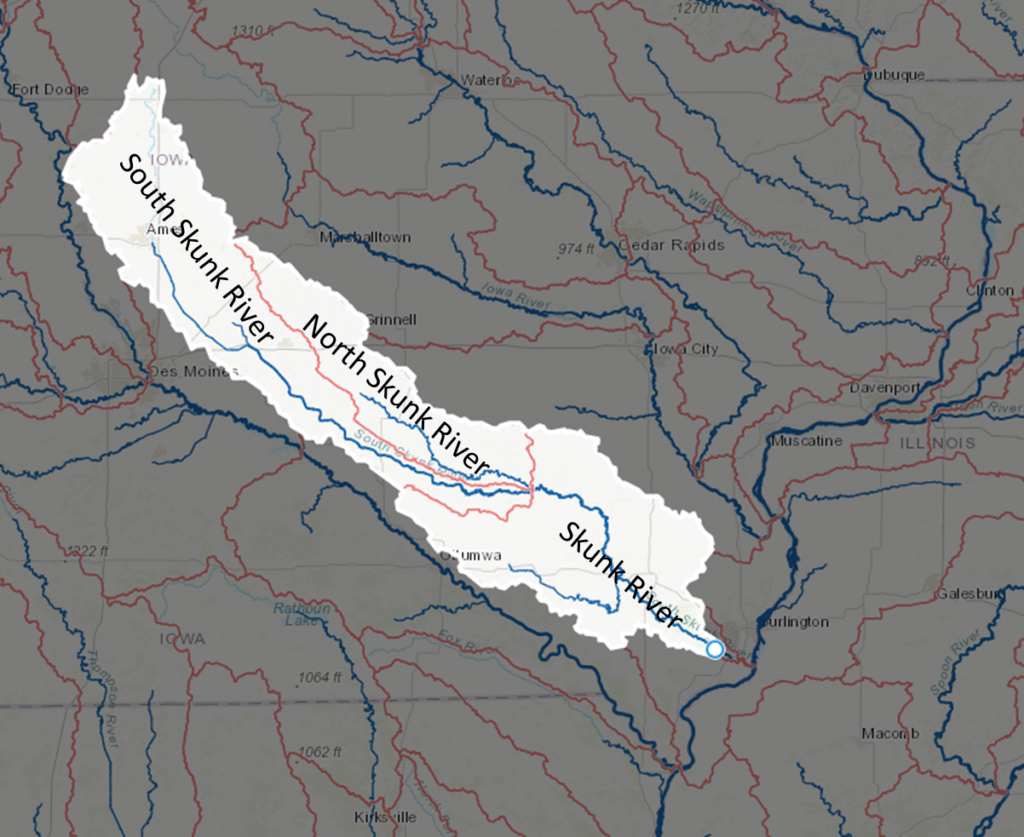

- The Skunk River starts near Blairsburg and joins the Mississippi River near Burlington after a journey of 274 miles. By that point, it drains more than 4000 square miles of central and southeastern Iowa.

- Thunderstorms in the Ames area lead to a rise in water levels at Augusta eight days later.

- Rain that falls in the watershed can reach streams quickly if it runs off the surface or travels through storm sewers or drainage tiles, but moves more slowly if it’s caught by ponds and wetlands or soaks into the ground. Some of the water entering Ada Hayden Lake in Ames showed chemical signatures of having been underground for more than 50 years!

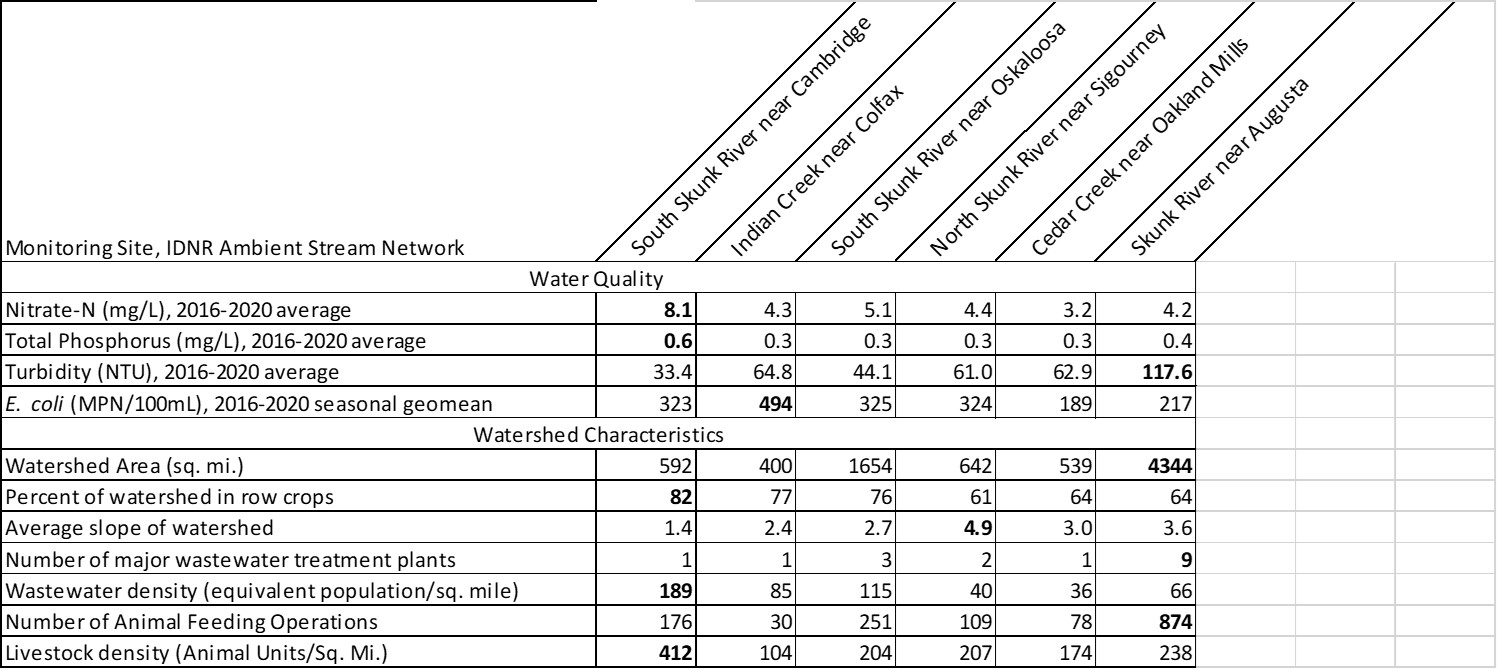

Watershed characteristics can help explain water quality patterns in the Skunk River and its tributaries, as shown in this table. For example:

- The North Skunk River watershed has steeper hills, so has higher turbidity levels. The South Skunk River watershed is flatter with more tile-drained cropland, so has higher nitrate.

- The Skunk River receives effluent from 9 major wastewater treatment plants (Ames, Newton, Nevada, Mt. Pleasant, Grinnell, Fairfield, Oskaloosa, Washington and Montezuma) and 85 smaller systems, which contribute to higher phosphorus levels.

However, the most memorable and sobering lesson about watersheds was taught by Lake Darling. We camped three nights at the state park, and I had an opportunity to explore it on Monday when high water levels kept us off the river. Lake Darling State Park has a lot going for it: a large lake in a beautiful setting, with an active Friends group that has improved trails and facilities. But the water quality is appalling. During my visit, the beach had a warning sign posted due to high levels of microcystin (a toxin produced by blue-green algae). I have never seen water this green. It looked like a kale smoothie and smelled like manure.

What happened? In 2007, Iowa DNR was celebrating Lake Darling as a success story, after most farmers in the watershed participated in a program to control erosion and intercept runoff. A $12 million project to drain and restore the lake was completed in 2014. By every indication, these efforts were successful at reducing the amount of sediment entering the lake. However, other water quality metrics (orthophosphate, E. coli, and microcystin) have gotten worse. The most likely explanation is the manure from 30,000 hogs. Nine animal feeding operations have been built in this watershed since the park reopened. I calculated the density of livestock in Lake Darling’s watershed (598 animal units per square mile) and found that it’s highest of any lake in Iowa, and higher than all but a handful of rivers.

This is why it’s not enough to measure success by dollars of cost share spent or the number of practices installed. We need to be aware of both positive and negative influences on the water bodies that we care about, and we need to test whether water quality is actually improving. At the Iowa Water Summit, I’ll share some tools and tips for doing just that. Hope to see you there!