Glitter in Your Grass: The Secret Lives of Fireflies

While the season of twinkling twilight in Iowa has nearly ended, fireflies (aka “lightning bugs”) live in Iowa year-round! What do you really know about these mysterious sparks of light? They are not just magical glittering displays – they are real insects that serve important ecological and medicinal roles and are threatened by habitat loss and light pollution. Nearly 30% of firefly species in the US and Canada may be at risk of extinction. But how can you support firefly populations? Where do they live? Should you collect them in jars? Here, we discuss all things fireflies, from their terrifying larval traits to their endearing embers of light. Read to the end for tips to attract fireflies to your yard!

Fire Beetles

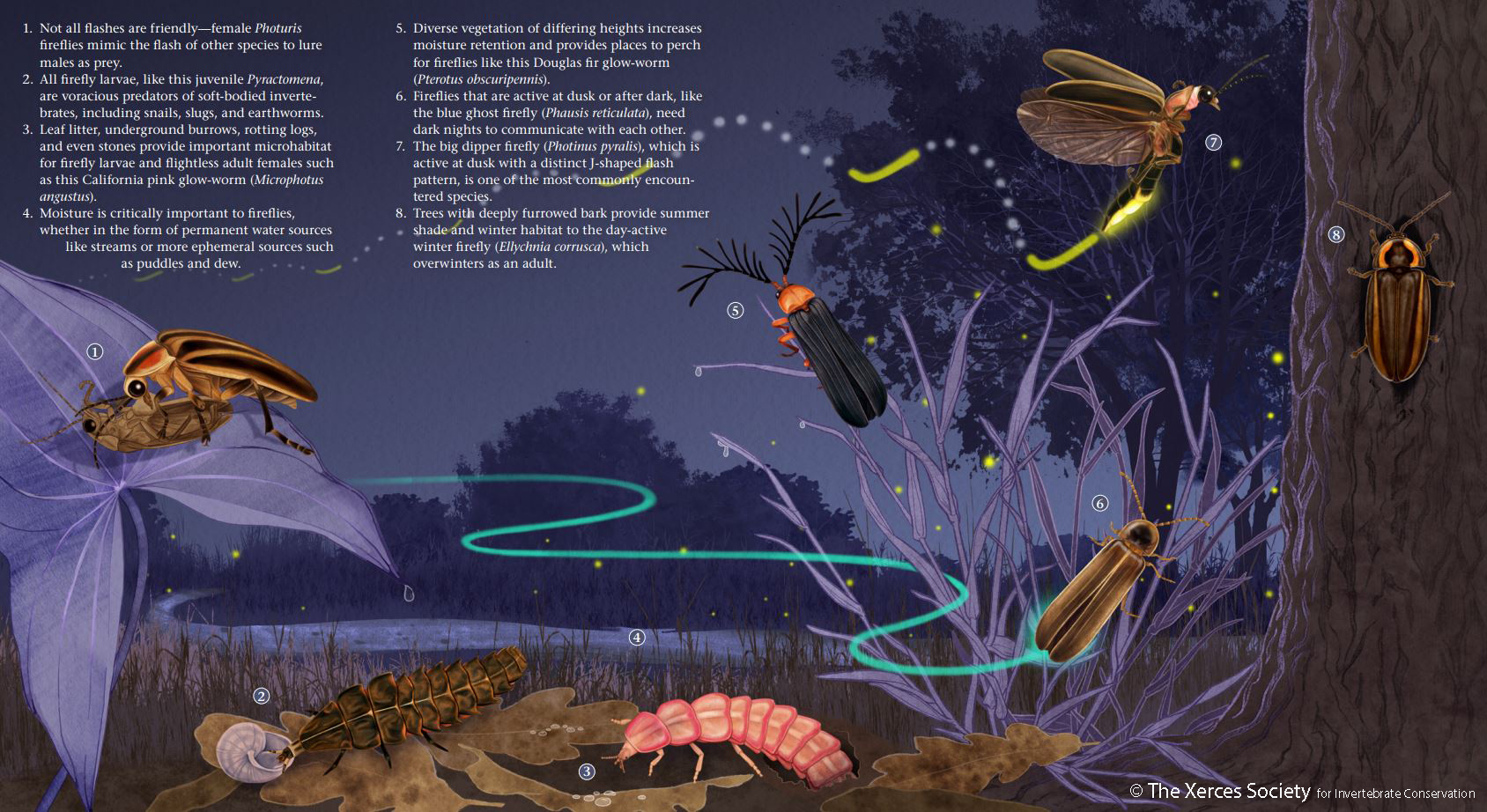

What is a firefly? Fireflies are actually beetles in the family Lampyridae. There are over 2,000 species worldwide, with about 170 in the US and Canada. Here in Iowa, we commonly have 7-9 with the potential to have up to 13 species(see Insects of Iowa and The Xerces Society – pg 4). Because most fireflies are nocturnal, we know very little about them despite their popularity. They go through complete metamorphosis, the same life cycle that butterflies and other beetles go through.

There are actually three kinds of fireflies in the world: flashing fireflies, dark fireflies, and glow-worms. Flashing fireflies are what we are most familiar with. They blink and glitter at dusk or during the night. Dark fireflies are active during the day and do not light up much, if at all. Lastly, glow-worms are fireflies in which the adult female looks a lot like it did when it was a larva (worm). They give off a near-continuous glow, giving it the name “glow-worm”. Male glow-worm fireflies look similar to the flying adults of dark and flashing fireflies. Iowa has mostly flashing fireflies, several dark fireflies, and so far has no glow-worm observations (but read here about another kind of glowing grub that can be found in Iowa).

Bioluminescence in Fireflies – and Our Food!

The firefly’s sparkle is created through a process called bioluminescence, which is the production of light by a living organism. There are few bioluminescent species outside of the ocean, so fireflies are pretty special! Flashing fireflies have an organ near the tip of their abdomen called the “lantern” where chemical reactions cause the enzyme luciferase to activate the light-emitting compound luciferin, causing the lantern to glow. Firefly light is one of the most energy-efficient lighting techniques in the world, with almost 100% of the energy used to emit light, and nearly zero energy lost as heat. In comparison, the most energy-efficient fluorescent bulbs give off 90% light and 10% heat. Firefly bioluminescence has been re-created synthetically since the 1980s, and has been medically significant for decades for identifying everything from blood clots to bacterial contamination in food. Fireflies, however, use their light to communicate to potential predators and lovers. For predators, their flicker warns that they contain a terrible-tasting compound called “lucibufagin” (more like luci-barf-again – ha!). For lovers, the glimmer means the firefly is looking for love.

Baby Fireflies

Fireflies lay their eggs in sheltered, moist places such as leaf litter, shallow tunnels, rotting logs, or moss. Some species’ eggs even glow! From the eggs hatch glowing larvae. They spend most of their lives (up to a few years) as larvae, living under or near the ground and hunting soft-bodied animals such as slugs, snails, earthworms, and grubs. Moisture is important for firefly survival – much of their prey requires moist soil. The larvae gorge themselves with soft-bodied victims, and are extremely beneficial in the garden, keeping food such as cabbages and strawberries safe from slugs and other pests. Firefly larvae survive winter if there is enough moisture and cover in the form of leaf layers, logs, mulch, rocks, or moss. Come spring and summer, the larvae pupate, and in a few weeks emerge as adult fireflies.

Adult Fireflies

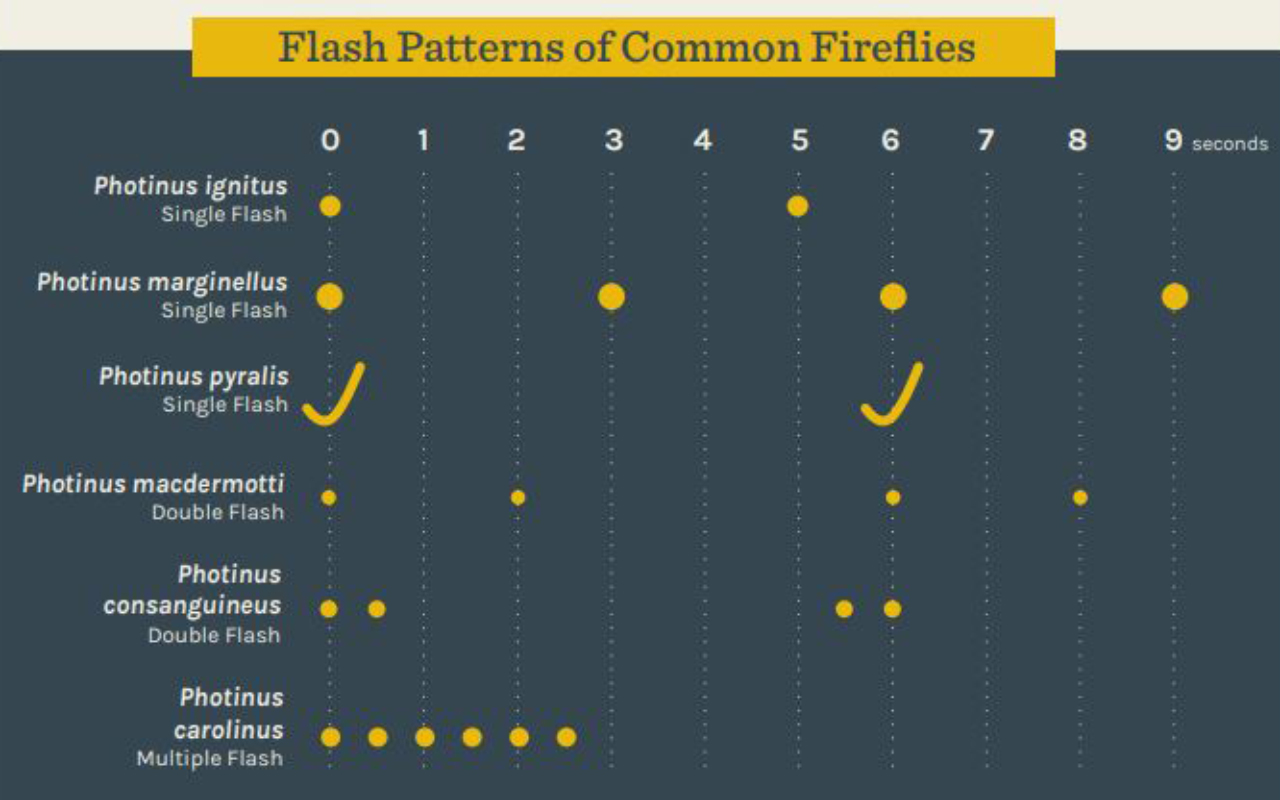

Because most adult fireflies don’t eat, their chief concern is finding a mate and laying eggs. For flashing fireflies, males fly around and blink to communicate with females. Each species has a unique flashing pattern (see the flash chart image below). The time of night, the duration of each flash, the height of the flash, and the pattern or shape of the flash come together to communicate the species, their sex, location, and willingness to mate. For example, the big dipper firefly emits a flash pattern that dips, making the shape of the letter “j”. For most species, female fireflies don’t move much. Many can’t fly at all and instead find a perch, respond with their own signal, and let males come to them. Once a male finds a female, they mate and the male passes a “nuptial gift” in the form of extra protein and nutrients to the female. This is important because most adults don’t eat, and the extra nutrients allow the female to be a more successful egg layer and ensure a healthier next generation. Depending on the species, mating displays can last anywhere from 20 minutes to several hours. These displays are special and are one of the few kinds of insect communication that humans can see with the naked eye and distinguish which species is “speaking”!

A flash chart for the different species of fireflies created by Mass Audubon, a nonprofit in Massachusetts that heads Firefly Watch, a community science program.

Femme Fatales

A big exception to normal flashing behavior is in a group of fireflies known as “femme fatales”. Females in the genus Photuris are deceptive and carnivorous. They purposely flash the signal of the female Photinus genus instead of their own. The male Photinus firefly approaches the carnivorous female, thinking it’s a friendly female of its own species. The Photuris female strikes and eats the male. Females eat males not out of spite, but to acquire the predator-repelling lucibufagin toxin that tastes bad. These femme fatales evolved to glow but did not evolve to create their own lucibufagin. Eating these male fireflies of a different species provides them with energy and the protective toxin.

Shine Little Glow-Worm (glimmer, glimmer!)

Less intense glow-worm fireflies are trying to find mates as well. The flightless, larvae-like females emit a continuous glow to attract flying males. Males have a weak glow, if any. They mate, and the male leaves unscathed. Lastly, the dark firefly group doesn’t glow much, if at all. As adults, these fireflies are active during the day so communicating with light is pointless. We all know how hard it is to see a flashlight or a phone screen on a bright day. So instead of flashing or glowing, dark fireflies communicate using chemical signals called pheromones.

Habitat for Fireflies

Fireflies need specific habitats to survive. Firstly, they need darkness. Over 75% of firefly species communicate at twilight or during the night by flashing or glowing. Artificial light from windows, garage lights, street lights, etc. contributes to light pollution. We have all witnessed light pollution – it is obviously harder to see the stars in the city versus the country. Fireflies have a similar problem seeing each other’s flashes through light pollution at night. This is a major issue because if they cannot find each other, they cannot mate and produce the next generation. Dark Sky International has great resources on this subject, including the graphic depicting light pollution.

Secondly, fireflies need their natural habitats. This means a diverse set of native plants with varying heights, including trees, undisturbed streams, and other water features. Plant diversity gives females different heights to perch on for mating, and water resources ensure a moist environment for larvae. So what can you do at home to support and attract fireflies?

Attract Your Own Light Show

To make your home firefly-friendly, lower light pollution. This is simple, and saves energy and money! It also helps migrating birds and moths. Use curtains, not just mini blinds, to seal light inside. Put outdoor lights on a timer or use a motion sensor. Opt for red or warm-colored light bulbs (or add several layers of a red filter to your current LED bulbs). Red light doesn’t bother wildlife nearly as much as white or blue LED lights. Trees can help shade out the glow of street lights, and lights that shade the light down rather than up and out also help. Ask your neighbors to take similar steps – light pollution doesn’t stop at property lines! Another simple step is to stop using grub and slug killers on your lawn and garden – they harm not just slugs and grubs, but the firefly larvae that feed on them. Mowing less helps a great deal and an easy step to take. Add native plants when you can. Add flowers, bushes, and grasses as you go to create different kinds of perches for female fireflies and safe places to hide during the day. Leave leaf litter and logs retain moisture and give overwintering fireflies a cozy place to stay. Fireflies aren’t very mobile (think of how easy they are to catch), and if something happens to their habitat, they are not able to move quickly to a better location, especially when they are larvae.

There are few pictures more nostalgic than fireflies in a jar. The amount of fireflies captured in this jar is a good amount – it’s not too crowded. Adding some leaves and sticks to perch on, along with a piece of damp paper towel, would make this jar even better.

Fireflies as Night-Lights

In my opinion, and the opinion of Dr. Sara Lewis, it is perfectly fine to collect fireflies in a jar responsibly. It’s great that kids and adults alike want to observe them closely! The best place to observe fireflies is a place with taller or native vegetation, with trees, near a river or stream. Start looking for flashes around dusk. Watch for different flash sequences and see if you can identify different species! Gently catch fireflies with your hand or a net and place them in a large jar with a damp (not sopping wet) piece of paper towel or a small piece of apple. You especially want to include a damp paper towel if your jar lid has “air holes” in it (fireflies can dry out quickly). I recommend letting captured fireflies go in the place you caught them before you leave or go indoors for the night. This is because Iowa does have carnivorous fireflies, and if you accidentally capture them and the kind of fireflies they eat, you will have an all-night feeding frenzy. Not the end of the world, but it can be upsetting. Also as previously mentioned, fireflies can dry out in the jar overnight. Lastly, if you caught the fireflies in a public place like a park, please let them go before you leave so that others can enjoy those fireflies – you don’t want to keep the magic from others.

If you catch fireflies in your own backyard and periodically want to wait until morning to let them go, you can learn ahead of time what the carnivorous firefly looks like and remove them before you go to sleep – they won’t bite and can’t hurt you. Also, don’t collect so many fireflies that they cover the sides of the jar. I remember waking up as a kid with a jar full of dead fireflies on my nightstand and feeling sad and guilty. Not overcrowding the jar and keeping it slightly moist will make firefly collecting a positive experience! Don’t forget to release your overnight guests in the morning in vegetation near where you caught them.

There is a sort of magic that happens when kids catch a firefly for the first time. However, these little jewels are real insects, with real problems we can help solve. We also don’t know much about these shining beetles, and need more community scientists reporting what they see. By reporting firefly sightings, choosing a few light-reducing options, and creating more native and pesticide-free habitats, we can experience the joy of watching fireflies each summer for generations!

More Resources and Fun Links:

Firefly-Friendly Lighting Practices (The Xerces Society).

The Firefly Atlas – Community Science by The Xerces Society.

Firefly Watch – Community Science by Mass Audubon.

Fantastic children’s book: The Very Lonely Firefly.

Dr. Sara Lewis’s website.

The Firefly Experience – an Iowan’s beautiful firefly photography and videos!

What are synchronous fireflies?

What are blue ghost fireflies?