Missing Monarchs, What it Means, Why it Matters, and How to Help.

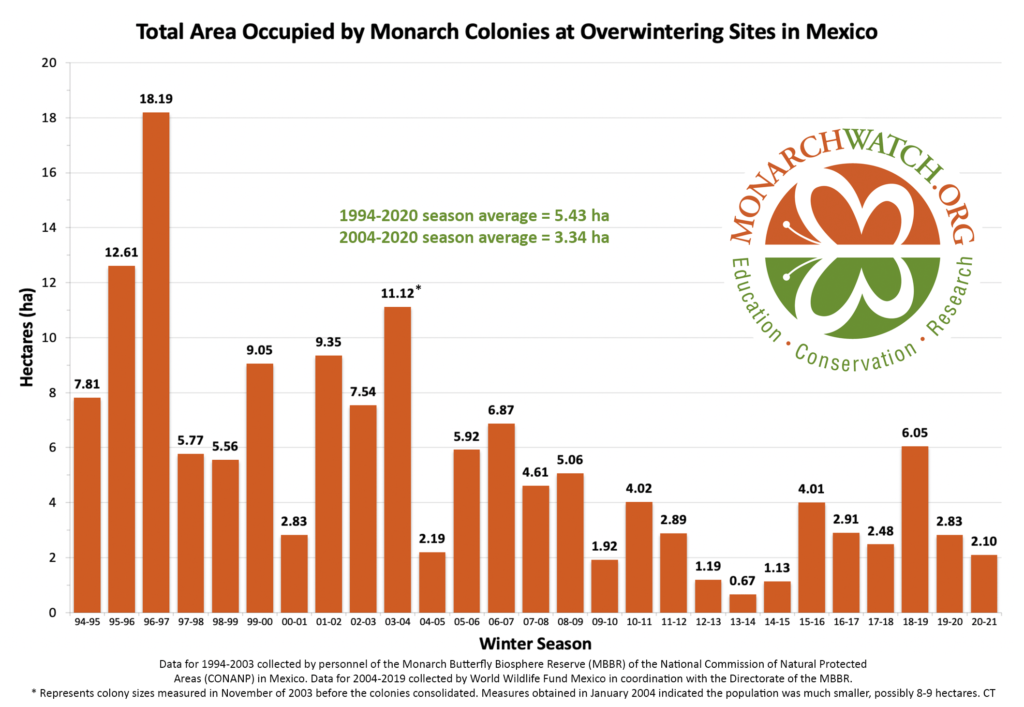

It seems to be a yearly event nowadays, that we wait with bated breath for the release of the year’s final monarch count from Mexico, where they spend the winter. Similarly, each year, we’re let down with the news that the population has fallen again. This same thing has happened this year, with MonarchWatch’s yearly report from the field. Yet again we’ve seen a decline, with the total area covered by monarchs in their overwintering site falling 26% compared to last year, now only covering 2.1 hectares (5.2 acres). For a comparison, the indicator of a healthy Monarch population is an overwintering area of 6 hectares (14.8 acres). So what’s going on here, and more importantly, what does it mean?

It’s time for my controversial but true statement, monarchs really aren’t good pollinators. There, I said it! They don’t contribute very much to fruit or seed production, and they certainly don’t help with our food security. So what’s the deal? Why are we spending our time and energy monitoring and reporting on them? Well, there are a lot of reasons why protecting them matters. For example, if you felt uncomfortable, angry, or saddened by any of my previous statements in these last 2 paragraphs, then that’s a fantastic reason on its own to protect them.

Monarchs have a special place in the culture of Iowa, the Midwest, and North America as a whole. Most people that I talk to about the plight of the monarchs reminisce about seeing them delicately flying around in the summer. Many more, myself included, have fond memories of raising and releasing Monarchs as part of countless elementary school science classes. For many people, monarchs were a great introduction to the wonders of nature, highlighting how creatures can grow and change through time in order to adapt to their surroundings. Monarchs also teach us about migration and animal movement, how creatures overcome great odds, and large distances all for the sake of the next generation, who in turn will repeat the cycle.

Outside of nostalgia, metaphor, and symbolism, monarchs have an important role in conservation as what’s called an indicator species. Because of their size, recognizability, and large range, tracking a trend in the population of monarchs is far easier than, say, a small, camouflaged, yet more-efficient pollinator. If we know that both of these creatures have similar habitat and dietary needs, it is in our best interest, time and energy-wise to focus on the big, orange, easy-to-track species. By providing the good habitat, food, and space for a monarch, we can expect other pollinators to use those resources in a similar way. Similarly, if we see declines in monarch numbers, we can use that data to assume that other species of pollinators are also declining for similar reasons.

It’s in our best interest to protect monarchs, because by extension, we’ll be protecting pollinators as a whole. Now you may be wondering how you can help monarchs and pollinators, what things you can do to help reverse these declines? The good news is that no matter where you live, or how much land you have, you can help your local pollinators. All it takes to start is a few seeds, easy enough right?

Well, no…you need to make sure you plant the right seeds for the job. Monarchs and pollinators evolved right alongside our native plants, so those are the plants to grow that will cover all of their nutritional needs. If you aren’t able to access native plants, or don’t have the space for them, non-native nectar plants like lavender, mint, and clover are all good options (just make sure that they don’t spread outside of a designated area!) Also plant “host plants.” These are specific species of plants that caterpillars will eat to prepare them for becoming butterflies. The host plants for monarchs are famously milkweeds, but every other butterfly has their own version of this. Finally, your plants should bloom throughout the season, with species blooming continuously between May and October. This way, you’ll know that you’re providing a source of flood for hungry pollinators at all times.

Monarchs may not be the best at pollinating, but they are an important symbol. They symbolize migration, change, and the cycle of nature. They also symbolize pollinators as a whole, illustrating their needs, their declines, and their need for protection. Again, by protecting monarchs, providing them with spaces for them to grow, thrive, and eventually venture out from, we’ll be able to protect all of our pollinators.