How to Start Caring About Pollinators: A Guide for Iowans

Now that the City of Ames has its own Pollinator Plan, we know how the city feels about Iowa’s native pollinators. But what about individual Iowans? We asked three central Iowans from vastly different backgrounds about how they 1) came to appreciate pollinators and wildlife in general, 2) what catalyzed their appreciation into action, and 3) how they stay energized and hopeful for the future of pollinators and our natural environment as a whole. Lori Biederman, Lynn Kellner, and Todd Burras share their journeys with us here.

A trout lily at Brookside Park, where Lori has spearheaded a Plant Corps with Friends of Brookside Park to remove invasive plants.

Lori Biederman – Ames, Iowa

I grew up on a 10-acre hobby farm in southern MN and both of my parents are biologists. I spent much of the summer playing outside. I was tuned into the natural world, but mostly for plants, and did not think too much about insects.

I started appreciating pollinators relatively recently. Although I have two advanced degrees in ecology, my focus has been on plants and the soil. Animals in general were just not my focus area. However, now when I’m outside working at field sites or in my garden, I like noticing the activity of birds and insects around me. This suits me as I get older and cannot move as quickly as I used to; plants don’t mind activity around them, however animals such as pollinators require sitting still and watching.

As an ecologist, my gardening philosophy aligns with my training – plants will sort themselves out to the conditions they like. Because native plants are adapted to local conditions, they are the easiest to grow! Now I have lots of plants to enjoy. My backyard is forested and unmanaged; I buy forest seed every year from Prairie Moon Nursery and spread it around – plants pop up when they are in a good place that matches their sunlight and moisture needs. Right now my backyard is full of purple giant hyssop and it’s covered with various bees, from big bumble bees to small little sweat bees!

I am in despair about the loss of biodiversity, but people can only appreciate what they know. I try to share my excitement about different organisms, and I am also learning new things too, which is always fun!

Lynn Kellner – Des Moines, Iowa

Growing up, my mother always had a yard full of flowers, fed the birds, watched butterflies, and loved the natural world. She was always reading, learning, and sharing. She inspired me, and I count it as one of her greatest gifts to me. No matter where I’ve lived, I’ve always had flower gardens, vegetable gardens, herb gardens, and bird feeders, and I’ve learned more as time has passed. I started deeply appreciating pollinators in 1981 when my then 5-year-old daughter and I searched a country road’s ditch for monarch caterpillars for a school project. As the class watched the caterpillars transform to butterflies, we learned all about milkweed, host plants for other moths and butterflies, and learned that some flowers are better than others for supporting bees, wasps, and other insects.

I started to become concerned about insects and bees when I learned about colony collapse disorder. Since then, I’ve become even more interested in pollinators, native plants, and other wildlife. I see myself as a realist, and that’s why I have hope during insect declines and climate change. I believe in the change of seasons, in science, and I believe in the goodness and perseverance of humankind. It may not be a direct line, but we will always keep moving forward.

Todd’s business, Wild Birds Unlimited, Ames, hosts many presentations about our native wildlife.

Todd Burras – Ames, Iowa

I grew up on a farm in north-central Iowa, with parents who took a great interest in birds, animals, insects, trees, and flowers. My dad was very active in implementing soil and water conservation practices, and he and my mom planted many windbreaks, shelterbelts, waterways, and bufferstrips. It was probably inevitable that I would adopt an appreciation for the same things in which my parents were interested.

Many things that raised my curiosity converged to eventually interest me in pollinators. To complete the Story County Master Conservationist program, I started a weekly outdoors page for the Ames Tribune that ran for over 20 years. While I learned about hunting and fishing, I was introduced to federal habitat programs that, while created to help pheasants and waterfowl, had the added benefit of providing habitat for songbirds, butterflies, amphibians, and other wildlife. But it was while learning about the native flowers incorporated in the seed mixes used in these programs that I became interested in prairie and the natural history of Iowa. Through this interest, I was introduced to an entire niche group of prairie enthusiasts that opened my eyes to the wonder of what Iowa was like prior to European settlement. The desire and urgency to learn more and to be actively engaged in conservation practices took root and has been growing ever since.

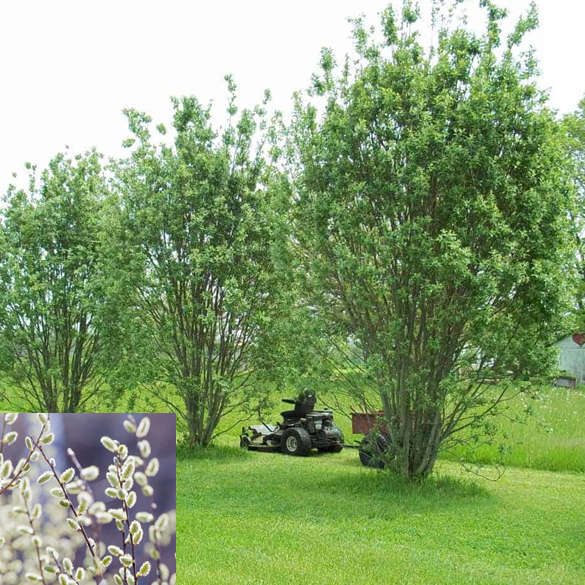

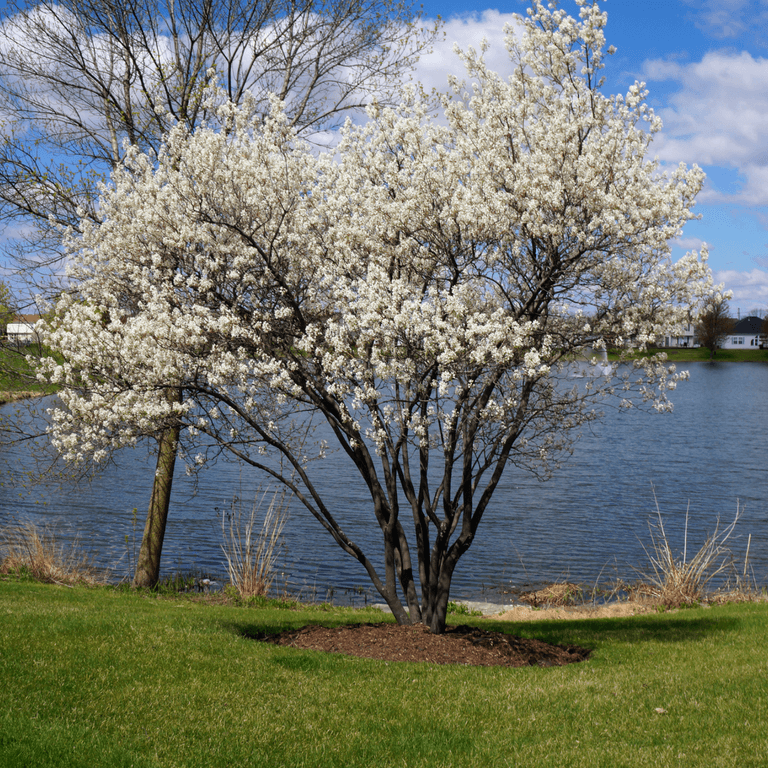

My wife, Stephanie, and I started supporting wildlife and pollinators by planting trees, shrubs, and flowers – not exclusively native ones at first. We eliminated pesticide use on our property, and Stephanie started keeping honey bees. I know that honey bees can be seen in a negative light, but they really were a “spark” insect that accelerated our interest in learning about and helping other pollinators and wildlife. Lastly, our deepening friendships with other conservation-minded people have been instrumental in our evolution of trying to become better stewards of the land and all creation.

In terms of insect decline and climate change, I’m encouraged when I see people make connections between their favorite birds or butterflies with their specific habitat requirements. Once that connection is made, they begin to understand how they can steward their land to provide for, and hopefully secure a better future for, the wildlife they are interested in and all creatures that play an integral role in the ecosystem. The pollinator project undertaken by Prairie Rivers of Iowa and the City of Ames is going to accelerate these connections for countless residents, and help change the trajectory of how our community grows more environmentally friendly for years to come.